If you have watched Django Unchained, directed by Quentin Tarantino, the dinner-table scene involving the notorious plantation owner Calvin Candie (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) is hard to forget.

During the exchange, Candie produces the skull of “Old Ben”, a Black enslaved man who had served his family for many years and examines it as part of a chilling display of supposed authority and intellect.

Candie then delivers an elaborate, pseudo-scientific explanation of how the skulls of Black people supposedly differ from those of white people; an argument steeped in racism and deeply flawed assumptions.

The scene is powerfully staged and unsettling, exposing the kind of spurious reasoning once used to justify slavery and racial hierarchy in the United States.

While the study of phrenology and craniology can be intellectually engaging and historically illuminating, they should never be used to imply the superiority of any race.

At their best, these fields offer insights into the evolution and shared nature of humankind.

In an article published on the Common-Place: The Journal of Early American Life website, titled “Were Fijians a race of their own or a mix of many?”, Ann Fabian offers a measured and objective account of how the skull of the Rewa chief, Ro Veidovi, the younger brother of the Roko Tui Dreketi, came to be displayed at the Smithsonian Museum, as well as the questions scholars sought to answer through its study.

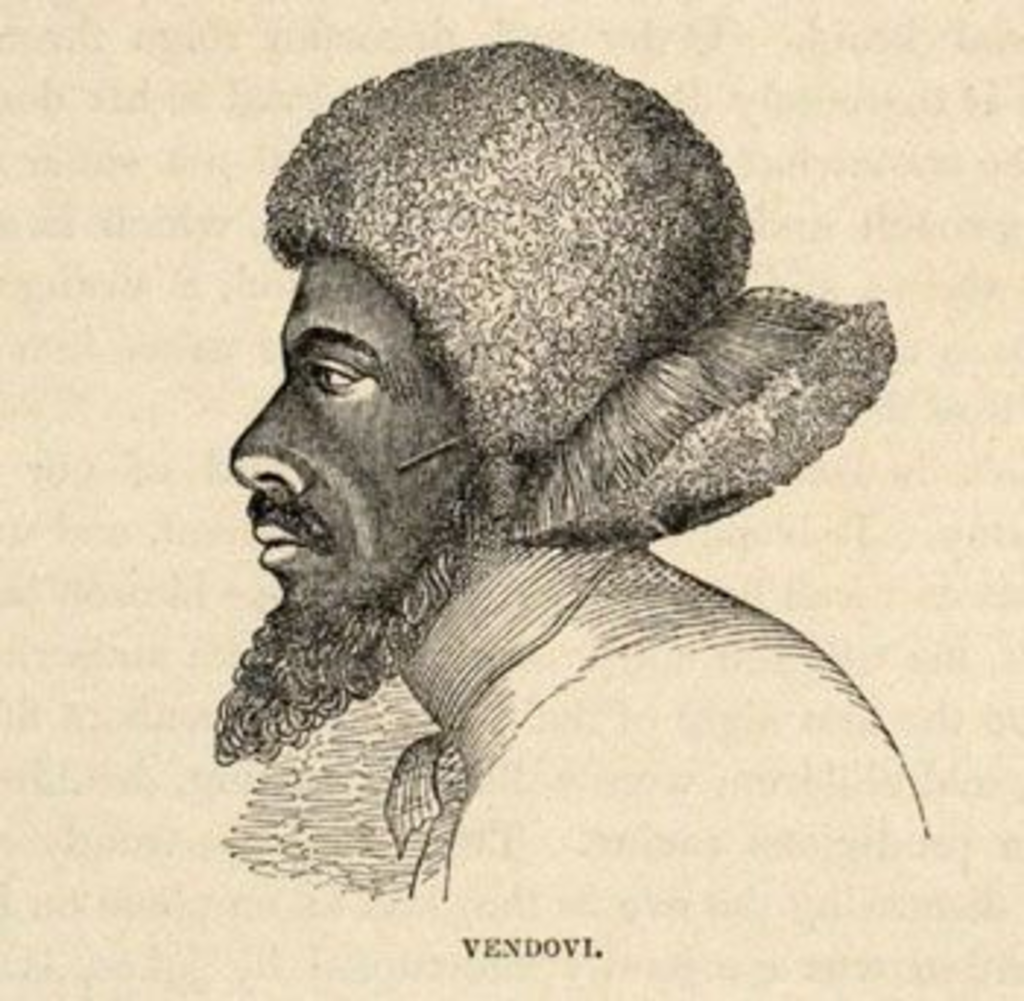

When the skull of Ro Veidovi was logged into a United States museum collection in the mid-19th century, it was reduced to a label and a number: Specimen 292.

Measured, catalogued and displayed, it became an object of scientific curiosity, stripped of context, culture and humanity.

But behind that catalogue entry lay the life, death and forced displacement of a chief whose story offers a sobering window into Fiji’s early encounters with American expansion, racial science and commercial exploitation.

From Fiji to a museum case

Ro Veidovi died in 1842, aged about 40, while being held prisoner aboard a ship of the United States Exploring Expedition.

His skull was taken, cleaned and measured, before beginning a long journey from Fiji to New York and then to Washington.

In museum records, he was described simply as “‘Vendovi,’ chief of one of the Fiji Islands”.

Visitors to the Army Medical Museum and later the National Cabinet of Curiosities were encouraged to view his skull as a scientific specimen, and few questioned how or why it had arrived there.

Earlier labels, however, were more revealing.

One collector had identified it as belonging to “the Feejee Chief and Murderer” a detail too sensational, and too political, to sit comfortably within a scientific display.

A prized ‘specimen’

The timing of Ro Veidovi’s death mattered.

As the expedition’s ships waited off New York’s Sandy Hook, naturalist Charles Pickering urgently summoned Dr Samuel George Morton, America’s leading skull collector and a pioneer of racial classification.

Morton was attempting to sort humanity into racial types, and Fijians presented a puzzle.

Dark-skinned and curly-haired, yet with sharp facial features, they did not fit neatly into the dominant racial categories of the time.

A living Fijian, Pickering believed, might help answer the question, were Fijians a race of their own, or a mixture of many? When Morton delayed, Ro Veidovi died, but even in death, his body was seen as valuable.

Detailed measurements were taken.

His pulse, height, head size and teeth were recorded. His head was sent to Washington while his body was buried in Brooklyn.

The man behind the measurements

Lost in these records was the human being.

During the long voyage from the Pacific, Ro Veidovi had formed close bonds with sailors.

He played music, shared stories of Fiji, explained local beliefs and became particularly close to pilot Benjamin Vanderford, a trader fluent in the Fijian language.

When Vanderford died, sailors recalled Ro Veidovi’s deep grief.

An island in Puget Sound was named Vendovi Island in his honour, a name that remains on maps today.

Yet this same man was also accused of masterminding the killing of 11 men involved in the bêche-de-mer (sea slug) trade in Fiji, an industry driven by American traders seeking profits in Chinese markets.

Trade, violence and arrest

By the 1830s, American interests in Fiji were growing.

After exhausting sandalwood supplies, traders turned to harvesting sea slugs, a labour-intensive practice that disrupted local economies, environments and power structures.

The deaths of the men working on the vessel Charles Doggett were blamed on Ro Veidovi and his kin.

Whether he acted out of political rivalry, resistance to foreign intrusion, or in pursuit of valuable whale’s teeth remains unclear.

What is clear is that his arrest was deeply flawed.

He was seized through coercion, tried on dubious testimony, publicly humiliated and taken away in chains, a warning, Americans believed, that killing a white man would not go unpunished.

Two worlds, two meanings

To Americans, Ro Veidovi’s capture was an assertion of justice and power.

To Fijians, it fitted into a very different framework shaped by prophecy, inter-chiefly rivalry and looming civil wars between Rewa and Bau.

A prophecy had foretold that one of the King of Rewa’s brothers would “float away”.

Ro Veidovi became that man.

News of his fate travelled back to Fiji, feeding into local histories at a time when violence, foreign interference and internal conflict were intensifying.

This checkered history of Ro Veidovi’s skull forces uncomfortable questions. Not only about racial science and museum ethics, but about the costs of early globalisation and empire-building.

Home at last

Saturday, December 13, 2025 will indeed go down as a momentous day in Fiji’s rich cultural tapestry.

After more than a century and a half in exile, Ro Veidovi finally returned home, not as a specimen or a curiosity, but as a chief reclaimed by his people.

His burial at Muaiqele in Lomanikoro marked a quiet yet powerful act of restoration, closing a chapter shaped by displacement and loss, and reaffirming the endurance of custom, kinship and chiefly authority.

As elders, family and the next generation stood together in solemn observance, the return of Ro Veidovi’s remains serves as a reminder that history, however fractured, can still be made whole.

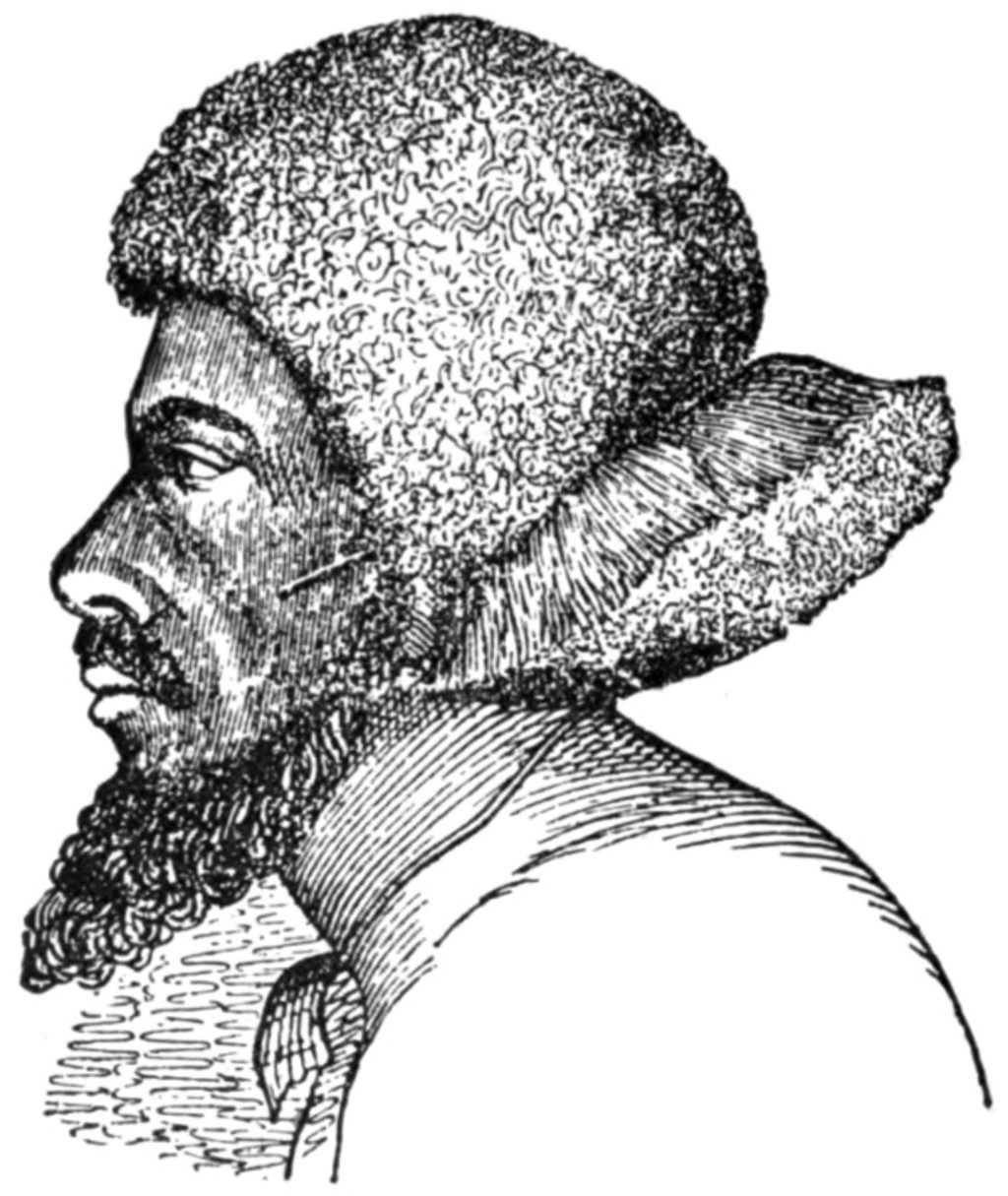

An artist’s sketch of the Rewa chief, Ro Veidovi Logavatu. Picture: WIKIPEDIA

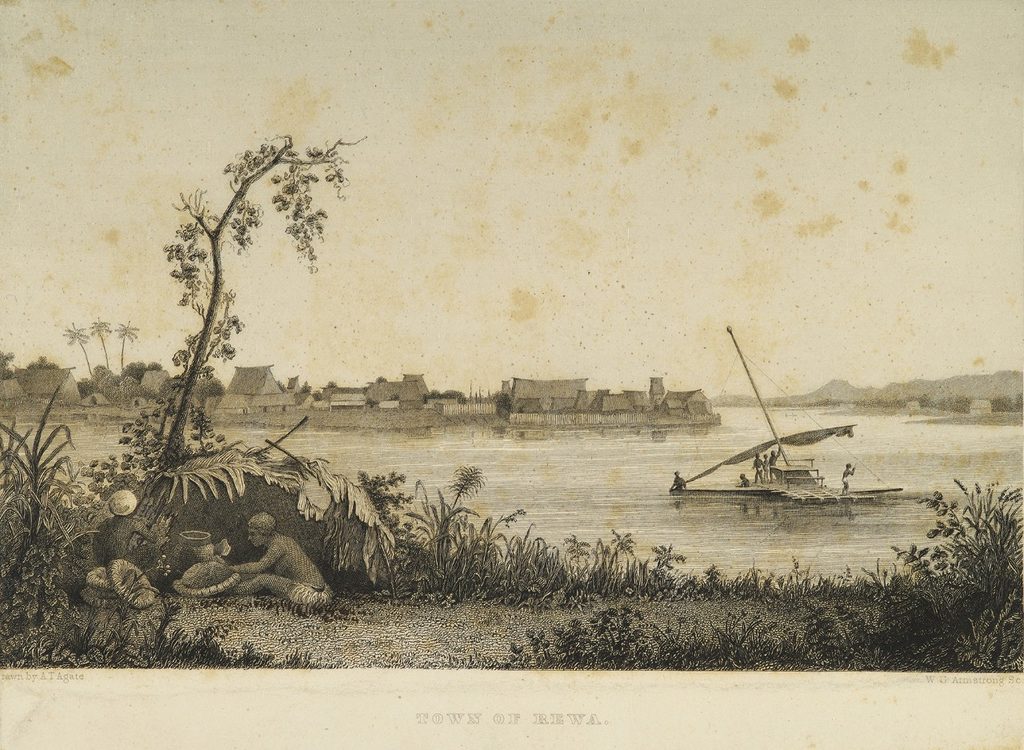

Artist’s sketch of the chiefly village of Lomanikoro on the banks of the Rewa River. Picture: WIKIPEDIA

Kavekini Utuutu carries the remains of Ro Veidovi to the chiefly burial site the sautabu at Lomanikoro village in Rewa on Saturday, December 13, 2025. Picture: JONACANI LALAKOBAU

Marama Bale na Roko Tui Dreketi Ro Teimumu Kepa leads the chiefly procession as Ro Alivereti Doviverata carries the remains of Ro Veidovi to the chiefly burial site the sautabu at Lomanikoro village in Rewa on Saturday. Picture: JONACANI LALAKOBAU

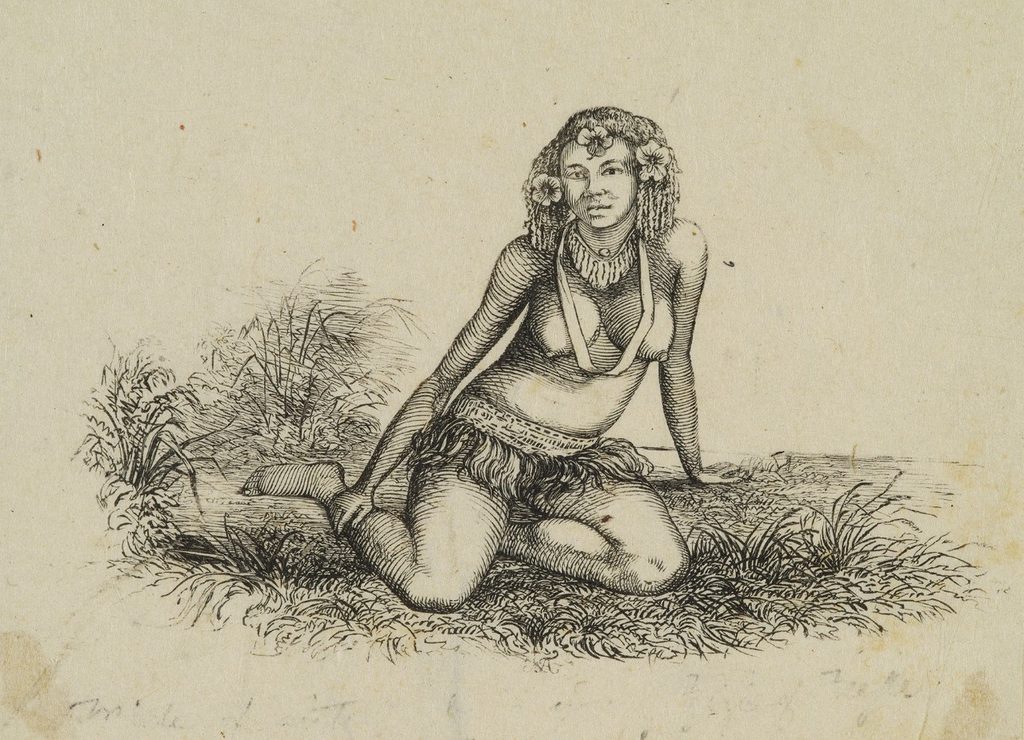

An illustration of possibly one of the wives of Rewa chief, Ro Veidovi. Picture: SUPPLIED