THERE is a strong sense of belief among a good number of indigenous Fijians, that the arrival of western Christianity did more harm than good to their ancient culture and way of life.

The arrival of the western church and missionaries resulted in much of ancient customs of the iTaukei being branded as demonic. It led to the destruction thousands of priceless artifacts, instruments, as well as ancient wisdom.

What vanished was not only ritual but a complex body of knowledge that once connected the iTaukei to their land, sea, and ancestors. As some elders now say, “We are poorer today for it.”

A spiritual order before the missionaries

Before the arrival of the church, iTaukei spirituality was founded upon a living relationship with the unseen world. Every village had a bete, a priest who served as the mouthpiece of the gods and ancestors.

The bete interpreted omens from the weather and natural world, advised chiefs on war and alliances, and offered healing and guidance in times of crisis.

He resided in the bure kalou, or spirit house, the heart of the village and the seat of divine authority.

According to an academic account from the University of Auckland’s Zachary Low, the bure kalou was always the tallest structure in any settlement, sometimes rising the equivalent of six storeys high.

This towering form, placed at the centre of the village, symbolised humanity’s reach towards the heavens, a tangible connection between the people and their kalou vu (ancestral gods).

Within its sacred interior were kept consecrated objects like ancestor carvings, priest’s dishes for yaqona, trumpets, and oil bowls. These were not mere decorations but instruments of power, used to channel the presence of the divine.

The Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology at the University of Canterbury records that such temples contained ancestor images carved from vesi wood or ivory, some bound with coir cord to “contain and channel” spiritual essence.

The moral code of the ancestors

Despite the missionary condemnation of these practices, a growing number of respected scholars and iTaukei thinkers argue that the ancient Fijian way of life already embodied the moral foundations of Christianity.

The concept of solesolevaki, working together in mutual care, mirrors the Biblical “love thy neighbour”. Respect for chiefs and elders echoes “honour thy father and mother”. Village laws promoting modesty and moderation reflected a shared sense of moral discipline. The protection of visitors reflected the compassion of the Good Samaritan, while the reverence for land and sea expressed a deep love for creation.

In essence, while the iTaukei may not have been Christians in the European sense, their social code reflected a profound spiritual harmony centered along the values and principles of respect, reciprocity, and divine order.

Colonial administrator G.K. Roth once wrote that chiefs would consult the spirits of their ancestors through the bete, who became possessed by divine presence during ritual consultations.

In many areas, the roles of chief and priest were intertwined, one providing temporal leadership, the other spiritual legitimacy.

In places like Bau and Rewa, this dual system evolved into two titles, the Vunivalu, or war chief, and the spiritual leader who upheld divine favour. Both were essential for ensuring crop fertility, peace, and the well-being of the community.

The same can be said of the island of Rotuma, where in the past, the island was led by two leaders who worked hand in hand and whose roles intertwined and were vital for peace and order. The secular leader was known as the Fakpure, while the spiritual leader was known as the Sau. It was the Fakpure who would install the Sau, women also served as Sau of Rotuma in ancient times and were known as Sauhani. The term ‘sau’ itself is a sacred term that had been used till today across Fiji, Tonga, Rotuma and much of Polynesia to describe blessings, good omens, and mana.

The priest from Nadi

One of the lesser-known episodes of this spiritual legacy is found in the story of a bete named Tomasi, from Navatulevu in Nadi.

When the young Ratu Seru Cakobau, future Vunivalu of Fiji, was exiled to Moala and later Matuku in Lau, he was accompanied by a priest from the western highlands called Tomasi. His role went beyond ceremony.

He served as spiritual guardian, counsellor, and protector, performing rituals to preserve Cakobau’s mana (divine authority) and connection to his ancestors.

Even after returning to Nadi, Tomasi’s influence endured. Oral histories speak of a bete who journeyed between islands carrying messages, prophecies, and blessings. Their constant travels gave rise to names such as Waqainabete, “the place of the priests” while the name “Moala” itself was later carried back to Nadi, marking the enduring ties between Fiji’s eastern and western spiritual centres.

Today, the memory of the bete and the bure kalou survives only in fragments and through names, ruins, and stories whispered by the elders.

Fiji’s ancient faith was not a typical system of worship which defines many world religions today, it was a way of life that bonded people not just to the natural world, but more importantly to one another.

Its legacy reminds us that the iTaukei were never without a moral compass or divine guidance before the arrival of the church.

History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor.

iBuburau ni Bete (Priest’s yaqona dish).

Picture: ART OF THE ANCESTORS

Early Fijians making their way up the Navua River. Picture: ART OF THE ANCESTORS

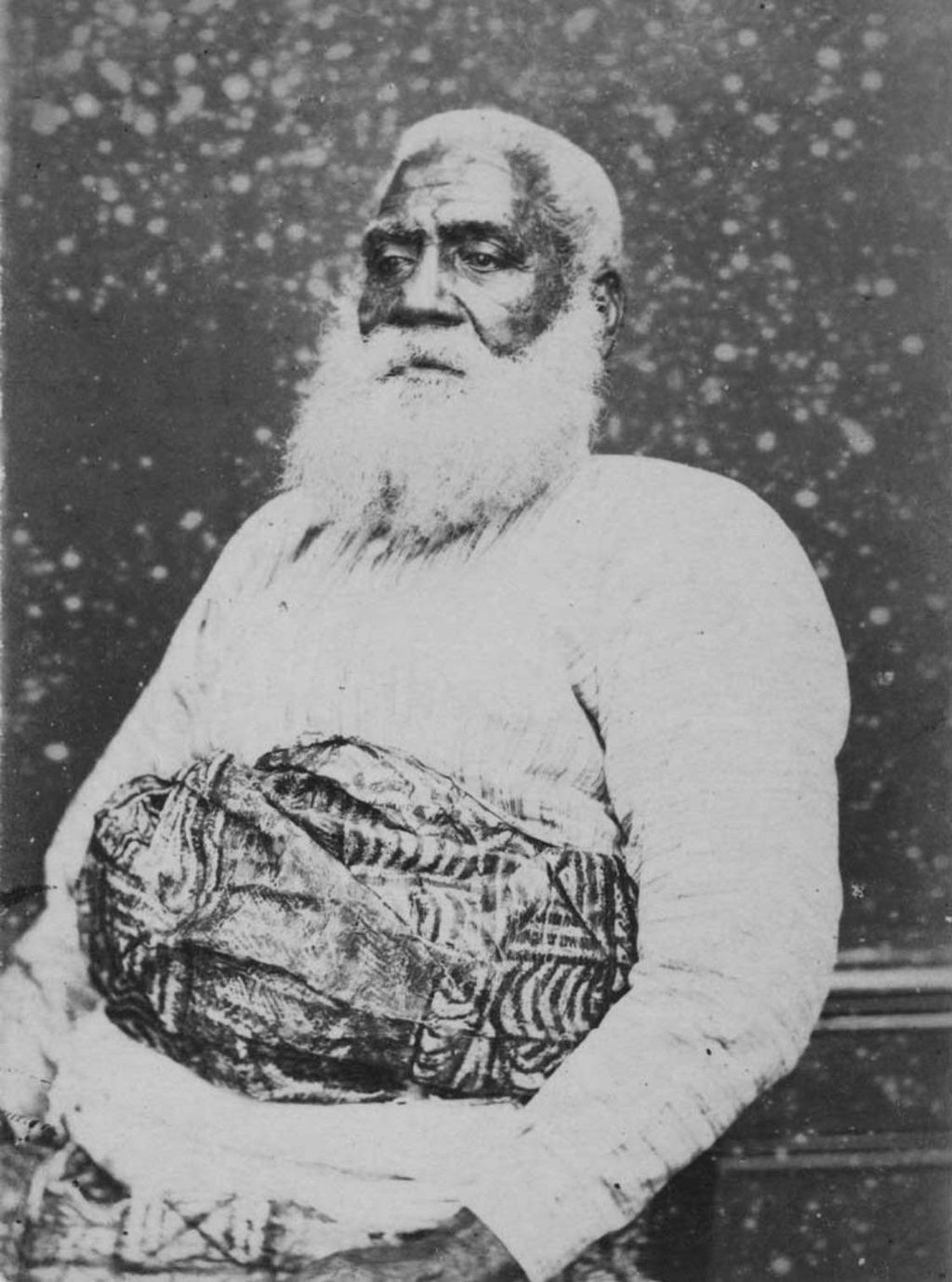

Vunivalu, Ratu Seru Cakobau who later took the Biblical name Epenisa or Ebenezer when he converted to Christianity. Picture: SUPPLIED

A bete sitting at the entrance of a bure kalou. Picture: ROGERS.PHOTO/INSTAGRAM

Firewalkers prepare the pit for a vilavilairevo or fire walking ceremony. The ability to do this lies only with the men of Beqa Island. Central to their preparations is the role of the bete. Picture: SUPPLIED