I’ve been feeling the tradewinds sweeping across my little patch of Fiji more noticeably in the last few days. With their steady, southeasterly, salt-laden breath, they cool the islands and hold the heat at bay.

Yet in their softening, one senses the turning of the seasons, the quiet handover to the warmer, heavier days of the cyclone season ahead.

That’s the thing about breezes — they carry an alchemy I can never quite name. Is it the soft susurration, the sighing undertone? Or is it the way they wander through the trees, coaxing leaves into sudden choruses of soothing sound? Perhaps it’s the way they brush against the skin, light as a whisper, stirring half-remembered moments you didn’t know were still with you. Whatever it is, they have the habit of turning fleeting thoughts into delicate tapestries of rich remembrance.

On top of this I’ve had the benefit of faint traces of woodsmoke and baigan choka (mashed eggplant) being blown into my room from a neighbour, an elderly widow, cooking on an outdoor stove using firewood. I love the combined smell: the charred skin of the eggplant as it peels away and the combusting wood. It has its own character: a sweetness at first, like sap or honey caramelising, followed by a darker undertone, earthy and resinous.

And so, at these times, my mind drops into a mongoose-hole of memory, slipping swiftly into hidden chambers of the past where small, bright fragments dart about, quick and elusive as the creature itself. In my reveries, shapes began to gather — places once familiar, faces halfremembered.

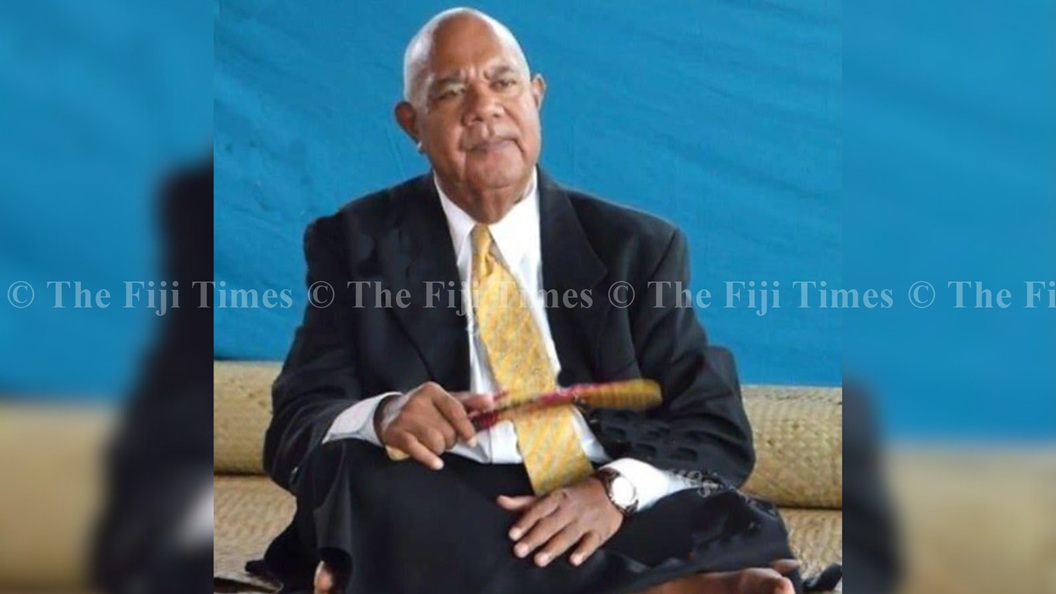

One presence stands out with quiet insistence: Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi, whose ninth anniversary of passing falls on September 29.

The details of Ratu Joni’s career — as Vice President of Fiji, Tongan noble, Chief Justice of Nauru, Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner in the Solomons, lawyer, judge and Roko Tui Bau — are all set out clearly online, so I won’t repeat them here.

I remember the day he died. Having reluctantly left Fiji after many years of legal practice, I found myself in 2015 teaching English in Matera, a hill town in southern Italy. Matera lies in Basilicata, the instep of the Italian Boot, a region stretching from the Tyrrhenian Sea in the west to the Gulf of Taranto in the south. It is one of Italy’s smallest, most mountainous, and least-known regions.

The land undulates through the verdant, grain-rich hills of the Bradano Valley, climbs into the jagged, forested peaks of the Southern Apennines, and drops suddenly into limestone gorges such as the one that cradles Matera. In the south-east, its most distinctive feature appears: the calanchi — barren, gully-streaked, fan-shaped hills resembling the surface of the moon, their soil crumbling in the hand like a soggy sandcastle.

On a sun-drenched evening, the calanchi shift in colour as though alive: from grey to burnished gold, then to fiery orange-red, and finally to cold ash-grey as the last crepuscular light drains into the night sky. It is a sight that once seen, never leaves you.

My teaching schedule was from 8pm to 10pm three days a week at a co-working space called Casa Netural, about ten minutes away on the corner of Via Galileo Galilei and Via Nazionale from where I lived in an apartment on Via Annunziatella.

A friend had lent me a car and so in the daytime, and especially on days when I wasn’t teaching, I would set out across Basilicata, winding into medieval hill towns, pausing to watch ancient festivals and losing myself in the region’s astonishing beauty. Everywhere I went I was met with warmth and generosity. Strangers would greet me and ask, “Di dove sei?” (Where are you from?). When I answered, “Fiji — in the South Pacific” their faces would light up with pleasing astonishment. And questions. There would always be questions. Curiosity and friendliness have the habit of piling question upon question.

Every so often I would check online news sites to see what was happening in Fiji. More often than not, I did so with reluctance, bracing myself for yet another report of the FijiFirst government’s assaults on rights and common decency or anyone who dared to oppose them. It was dispiriting and I preferred to do without bad news.

On the evening of September 30, 2016, I left my apartment and set out for Casa Netural. It was a Friday, and I was looking forward to teaching and to the promise of plans with friends over the weekend. I had barely reached the pavement outside when I pulled out my phone to check for Fiji news. A headline stopped me cold: Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi dies.

I rocked back on my heels and steadied myself against the wall. Shock gave way to a pang of guilt — I had not kept in regular touch with him. Our last exchange was an email on March 21, 2014. He had written that he was back in Fiji after two years with the Solomon Islands Truth and Reconciliation Commission, taking on consultancies as they came and moving at his own pace rather than by the dictates of the clock. He was living in Bau, travelling into Suva once a week, enjoying the calm away from the city’s bustle. With elections looming, he hoped they would be free and fair.

He closed with words that linger still: “I hope you are happy… but if not, that this ‘exile’ is as short and temporary as possible for you and yours. Insha’Allah. Stay well, regards … moce mada, Joni.” In an earlier email he had begun simply: ‘assalaamualeikum and bula namaste.’

That was Ratu Joni all over: always humble, always inclusive. Even in his greetings he reached across faiths and cultures, as if to say: whoever you were, you belonged; your presence mattered, your story mattered.

In the Wikipedia entry for Ratu Joni, it reads: “Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi, Lord Madraiwiwi Tangatatonga.” It was the “Lord” that caught my eye and made me smile wryly. Perhaps it was the best translation of “Ratu”, yet it seemed ill-suited to him — so unassuming, so utterly without pretence. “Lord? Me? Never!” I can almost hear him say. ‘Ratu, perhaps, yes, because I have chiefly titles and obligations — but Lord? Good heavens, no!’

Were he still with us, I can imagine him giving a quiet chuckle at the thought — that rare, tremulous laugh which lingered in the memory precisely because it was so seldom heard. More often, he simply beamed radiantly from ear to ear, the dignity of a Fijian high chief running quietly, almost invisibly, through him.

My earliest memory of Ratu Joni is from a Law Society conference along the Coral Coast. I’m not certain of the date, but I suspect it was towards the end of 2003, which was usually the conference season. This makes sense, as he had resigned from the judiciary after the 2000 coup and joined private practice with the Suva law firm Howards. Early that year, the British writer 3 Adam Nicolson had published a book called God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible, and I had brought it with me to read between breaks at the conference talks.

Before the start of one session, I noticed Ratu Joni sitting alone at the back and having asked permission, I sat down beside him keen to engage his formidable mind in conversation. He saw my book and we instantly launched into a lively conversation about what the Americans call ‘The King James Bible’ and the British ‘The Authorised Version’. As the conference talk wasn’t very interesting, we continued our conversation in quiet tones, often scribbling notes to one another.

The King James Bible, or KJB as it is often known, was first published in 1611. It remains one of the pinnacles of English literature — a towering monument of prose. Commissioned by King James I of England, it was the collective work of a team of scholars to craft a version of the Bible that rings with rhythm, majesty and imagery. In the English common law, biblical references from the KJB have historically crept into judgments especially in the Chancery courts where morality and equity overlapped. Lord Denning, one of the greatest legal minds of the twentieth century, who presided over the famous sugar cane contract dispute in Lautoka in 1969, would often sprinkle his judgments with echoes of the KJB.

From time to time, I’ve attended Sunday services at Coronation Methodist Church in Lautoka, sometimes taking my mother along. The minister, with great kindness, would translate passages from iTaukei sermons into English for our benefit. Yet what drew me there was the singing.

The Fijian choir, in full voice, is one of the most moving experiences one can ever witness.

Their harmonies rise and swell like ocean surf, carried on voices that seem to come from somewhere deeper than the lungs. The sound trembles through the church rafters, through your bones, through your very skin until goosebumps shiver across your arms.

That same sense of awe and uplift is what I feel in the cadences of the KJB. Its rhythms strike at the same place in the soul. And Ratu Joni felt it too. He loved the KJB.

“What does the language remind you of?” I asked him in a note. “Shakespeare? Wordsworth?” he suggested.

“Yes, yes, that too,” I replied, “but something closer to home.” “What did you have in mind?” he asked.

“A Fijian choir!” I wrote.

He threw back his head and smiled. “You’re right! I had never thought of that!”

We carried on our conversation after the conference talk, continuing over afternoon tea.

Passages from the KJB flew back and forth between us, interwoven with some of his favourite Fijian hymns, which he delighted in sharing with me. I knew then that I had found something very special in him. And in the years that followed, whenever we met, his eyes would light up as he recalled that first exchange on the KJB and the splendour of Fijian choral singing.

For all his love of such things, Ratu Joni also cultivated a formidable reputation throughout his life as a steadfast champion of racial harmony and the rule of law.

In the uncertain years after Fiji’s coups, he called on the nation to rise above ethnic divisions through respect and a sense of shared destiny. From the Parkinson Memorial Lecture in 2001 to the National Federation Party convention that same year, he spoke of statesmanship rooted in inclusivity and a democracy large enough to embrace every community. As the decade unfolded, his voice deepened in urgency and scope. To the Rotary Club he warned against apathy in a diverse society; at a Hindu gathering he urged prayers that honoured all faiths; before the Fiji Law Society he reflected on insecurities common to every community; to Xavier College cadets he celebrated the richness of culture.

By 2006 his appeals became more insistent: calling for contributions to unity, an end to racial voting and praising Indo-Fijian representation in society as vital to the nation’s well-being.

Threaded together, these speeches carried a single vision — Fiji as a glittering brocade of differences to be celebrated, resilient against division and sustained by the dignity of inclusion.

Equally unshaken was his faith in the rule of law as the nation’s surest safeguard. In 2005 he reflected that, though repeatedly battered by coups, it had grown stronger by “weathering sustained assaults”. That same year he reminded his audiences that law was no abstraction, but a practical check on power — and that its truest guardian was not the state but the people themselves, willing to defend and uphold it.

A decade later, he wrote of democracy as the “antithesis of arbitrariness,” untidy and complicated by design, because it was grounded in checks, balances and respect for rights. He was right. That untidiness is not a flaw but its strength: the messy give-and-take of public debate, the long pauses of consultation, the friction of disagreement, weary patience of compromise. It was the clamour of many voices learning to live together without resorting to force. In its slowness and imperfection lay its true genius.

In every forum and in every register, his message remained constant: the rule of law as both shield and compass, and the people of Fiji as its custodians. His words endure as a summons — to vigilance, to fairness and to the hope of a shared future.

A lasting image will always be his unshakeable decorum. Nothing could ruffle his feathers.

When he was unceremoniously dismissed from his position as Vice-President of Fiji on December 5, 2006, during the military coup led by Commodore Frank Bainimarama, he was forcibly evicted from his official residence the next day. All accounts suggest he did so with stoic calm. In any event, you didn’t read or hear of him expressing his outrage at such heavyhandedness.

Every so often, small signs remind me that he would be proud of where Fiji stands today: by fits and starts, democracy and the rule of law are strengthening. Progress may be snail-like but it is happening.

In August, the Fiji Sun reported that refugees from Africa and Afghanistan had “found safety, jobs and hope” here — thanks to Fijian compassion. At my gym, I often meet a group of Namibian friends, and our conversations about their homeland fill me with delight.

And then, just the other week, I passed the main mosque in Ba and noticed a huge banner hanging from the commercial building next door, announcing a Christian evangelical crusade. As I took a photo, I paused and thought: Ratu Joni would have cherished all this.

- AZEEM SAHU KHAN is a barrister and solicitor with Matera Law, based in Ba.