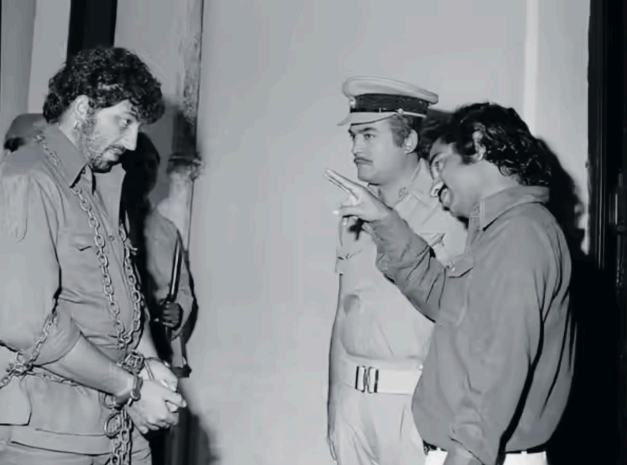

THERE is a moral ambivalence or duality in the two buddies and hired guns, Jai and Veeru, who are petty criminals who have spent time in most jails around the country. But Thakur sees good in them, and in the end, their good selves come out, restoring order to the world out of synch.

The same ambivalence is found in the Thakur character played by the late Sanjeev Kumar. Thakur is a model police officer and landowner, but one who doesn’t become squeamish when it comes to using brute force to exact revenge. In the original version of the film, Thakur crushes Gabbar to death with his nail-studded shoes. The censors objected to the excessive violence and insisted that it be changed. Sippy and crew rushed back on location to reshoot the ending. In the revised version of the film, Thakur leaves the fate to the authorities, again restoring a sense of morality and order. As an aside, the original and fully restored version of Sholay had its world premiere at Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna, Italy, on June 27, 2025.

In the first week of its release, Sholay was declared a box office flop. In the third week, it did one of the most amazing turnarounds in Bollywood film history. Not only were theatres packed to capacity, but the audience was participating by reciting every line of dialogue as the film went on. Ramesh Sippy himself, who was earlier in a state of deep depression with the knowledge that Sholay had bombed, was deeply baffled by this change in fortunes. Then he, like others, realised the reason for the turnaround – the reaction to Sholay’s dialogues was extraordinary.

The dialogues — from one-liners to entire chunks from scenes — took hold of the film-going public’s imagination. Polydor Records decided to capitalise on this by releasing a fifty-eight-minute record of selected dialogue. The record proved to be very popular, and the company couldn’t keep up with demand. Anupama Chopra says: “Sholay’s dialogue has now become colloquial language, part of the way a nation speaks to itself. Single lines. Even phrases, taken out of context, can communicate a whole range of meaning and emotion.”

I want to talk about important moments in the film that demonstrate the concepts of harmony/disharmony and the appeal to nationhood. These are mythical ideas that go back to the foundational texts of Hinduism, and India’s artistic artefacts have been built around mythical concepts. In fact, the whole idea of India has been built around a myth – the myth of national oneness.

The first is the scene where Ahmed, the Imam’s son, comes back to town slung on a donkey. The first part of that scene consists of a montage of shots, which show the prevailing harmony and order in the village. At another level, this montage can be interpreted as a metaphor for an imagined harmony of the nation. Here, one gets the microcosm view of the nation or the nation in miniature, with the different individuals plying their trade. The screen gives this order, and the various sounds become rhythmic and almost poetic. And then this order is shattered by the arrival of Ahmed’s body, murdered by Gabbar.

Basanti leads Imam (a Muslim) to Ahmed’s body, which carries a letter from Gabbar, threatening worse retaliation if Veeru and Jai do not surrender. As Imam weeps over his dead son, the villagers angrily tell the Thakur that they cannot make any more sacrifices and that the hired hands must surrender themselves to Gabbar. The Thakur tries to motivate the mob by saying that “he would rather die with dignity than live in shackles”. This is quite ironic, coming from the Thakur, who is part of the landowning class and to whom most of the village peasants are shackled.

Next, the Imam shames the villagers by asking Allah why He didn’t give him more sons to sacrifice as “martyrs” for the village. Again, in other discourses, Muslims are read as enemies of the Indian nation. But in this scene, communal harmony reigns. The disaggregated strands Mishra says “are reaggregated around an idea – that of the Mother …” A similar appeal to a sense of primordial oneness and ancestral longings is invoked by the actress Nargis in Mother India when the citizens are leaving. Again, it is a Muslim (Nargis) who is making the call. Such calls have resonated at a deep level with Indian audiences.

One can also read this binary of disharmony/disorder on one side and harmony/order on the other in the Holi (festival of colours) scene. The villagers get together in communal harmony to celebrate Holi. There is, of course, song and dance to celebrate the ancient festival as an affirmation of the continuity of tradition, but also as a marker of a minor victory over the forces of evil (Gabbar Singh’s gang). Hindus dance with Muslims and friends with foes. I quite like what Laurel Victoria Gray in “Hooray for Bollywood!” has to say about this: “Perhaps the popularity of Bollywood resonates with our desire for tribal identity, our dreams of a global village where everyone miraculously knows the same songs and dances.”

What Mishra says about the village in Mother India, that “rural India continues to function as a sign of cultural continuity”, is also applicable to Sholay. The same primordial oneness and pastoral harmony is found in Mehboob Khan’s “Aurat” (1940), “where peasants sing folk songs and celebrate Hindu festivals, notably Holi”. The pastoral harmony in Aurat is broken by the arrival of Gabbar Singh and his gang. Gabbar Singh again represents a force of destabilisation of the communal harmony that exists in the village as well as a threat to time-honoured traditions. But later, when the Thakur’s hired hands get their own back, order is once more restored.

Sholay was released in Fiji in November 1976 and captured the nation’s imagination. Days after its release, dialogues from the film were being recited by children in playgrounds and by adults in workplaces. Generations of Indo-Fijians (and even iTaukei) grew up watching the movie (some as many as twenty or more times) and learning every bit of dialogue by heart. Sholay was not just a film; it was a once-in-a-lifetime movie event, a crucial moment in Indian cinema. One of the stars of the film, the actor Dharmendra, said, “Sholay is the eighth wonder of the world.” The legend of Indian cinema, Amitabh Bachchan, described Sholay as “an unforgettable experience”, adding that he had “no idea at that time that it would become a watershed moment in Indian cinema.”