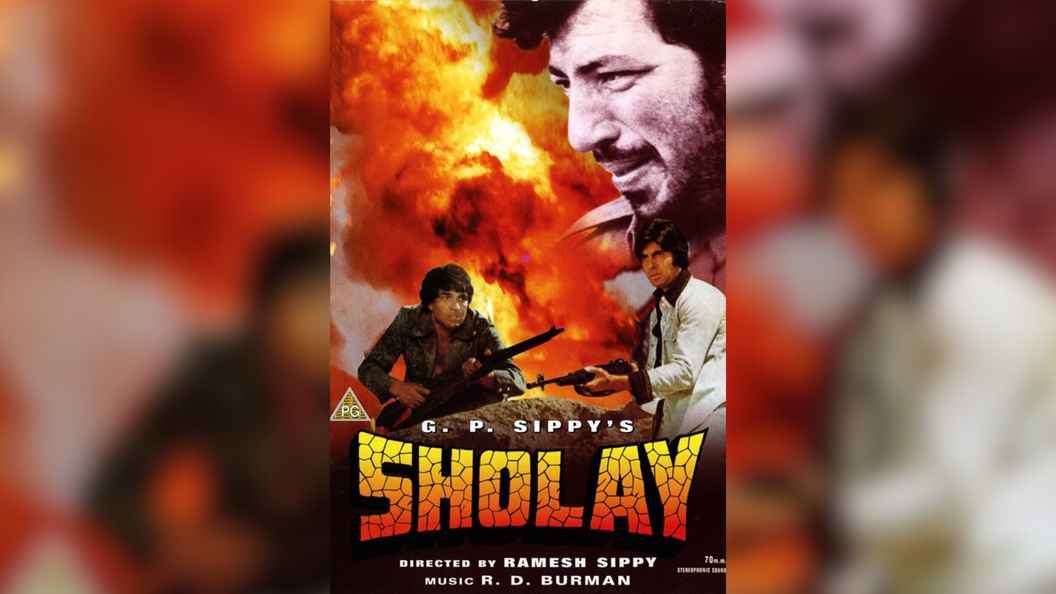

Over the years, many films have caught the Indian public’s imagination, but none bigger than Sholay, a super-duper (keeping in style with the Indian filmic tendency for hyperbole and exaggeration) event in Indian film history.

The film was released in India on August 15, 1975, and made box-office history, running at Delhi’s Minerva theatre for over five years.

The filmmakers used many unconventional cinematic elements, and it was the first Hindi film released in 70 mm with stereophonic sound.

Such was the film’s hold on the imagination of the Indian masses that in 1999, BBC India declared it “the film of the millennium”.

Bollywood is a chaotic melange of song, dance, comedy, melodrama, or, as Vijay Mishra says, using a term from Christian Metz, a grande syntagmatique, with its own conventions in the same way that Kabuki or Noh theatre are distinct art forms.

One of the greatest influences in the shaping of the genre has been Hindi mythology.

Bollywood has given many religious films like Jai Santoshi Ma (1975), but even in secular films, mythology exerts a powerful influence on style, story and theme.

Such is the case of a movie like Rajneeti (2010), which was a retelling of the Mahabharata within a contemporary political setting.

The other influences on Bollywood are Sanskrit drama, the traditional folk theatre of India, Parsi theatre and Hollywood musicals.

For a nation of such diversity, this style, called “masala” cinema, is most suited to capture the rhythms, ebbs and flows and many moods of the Indian nation.

Though Bollywood churns out hundreds of these masala films each year, only a handful find success at the box office.

It is the films in which all the elements are in perfect harmony that capture the public’s attention and find box office success.

Sholay has been such a film.

The script, written by Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar, is a suturing of other narratives, cinematic styles and motifs, chief among them the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone (Sholay was called a curry western by many critics at that time).

The massacre of the Thakur’s family by the villain Gabbar Singh has shades of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in The West (1968) as well as John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). Akira Kurosawa’s classic The Seven Samurai (1954), where villagers hire a group of mercenaries to rid the village of ruthless bandits, is perhaps the greatest influence on Sholay.

There are little moments from the film that have been borrowed/inspired by other films: the idea of friendship of Jai and Veeru, is an inspiration from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969); the double-sided coin used by Jai is similar to the coin used by Marlon Brando in One Eyed Jacks (1961); the character of the villain, Gabbar Singh, though modelled on a real-life bandit famous in the villages around Gwalior in the 1950s, was reworked around the character of the Mexican bandito played by Gian Maria Volonte in For A Few Dollars More (1965); the jailor character played by Asrani was inspired by Charlie Chaplin’s take on Hitler in The Great Dictator (1940).

For all the vast influences that have shaped Sholay, the film is not a copycat, but an original.

For those of us aware of the scale of Sholay’s success and what it means to Indians around the globe, let me quote from Anupama Chopra: “(Sholay) is not merely a film, it is the ultimate classic; it is myth.”

It has all the ingredients – action, romance, song, dance, melodrama, and seduction – that audiences expect. The dialogues are memorable, and the characters are real, but at the same time larger-than-life.

At the time of release, some ideas and developments used by the filmmakers were new to the Indian cinema-going public, such as the especially co-ordinated action sequences, unique camera-work, the aestheticisation of violence and the use of stereophonic sound.

But it all began with the script and the skill with which the writers brought the chaotic multiplicity together.

Like Hindu mythology, where the concepts of harmony and disharmony are significant motifs, all the elements within the film are in perfect harmony.

This concept of harmony is essential and operates on several levels. There is, of course, the order and harmony in the script, but the film was permeated with the mythical ideas of order, harmony, and nationalism.

These motifs have also been the raison d’être of many successful Bollywood films such as Mother India (1957), Border (1997), Kranti (1981) and Lagaan (2001) Sholay initiated two critical turns in Bollywood regarding the position of the scriptwriter and the approach to scriptwriting. Salim Khan, one of the writers of Sholay, said in Bollywood at that time (1970s), “heroes, directors, producers were the zamindars (landowners) and writers were the scheduled caste”.

He explained that that position was unacceptable to him and his writing partner, Javed Akhtar.

He said hey met up with director Ramesh Sippy and expressed their dissatisfaction, and their plea was heard.

This, Anupama Chopra explains, “set the stage for a whole new development in popular Hindi cinema” where the place of the writer became important.

The development in scriptwriting must be understood in the context of the radical difference in the way in which Hollywood and Bollywood screenwriters approach their craft.

For the Hollywood writer, the script is an organic artefact where the elements, such as character and structure, are put together tightly following, usually, the classical design suggested by Aristotle.

But the approach of Bollywood writers is piecemeal. A story is sketched out, scenes written and bits of dialogue fleshed out (observe the credits in a Bollywood film and one will see ‘script’ and ‘dialogue’).

But the Sholay script was tightly written, an organic whole, with order and balance.

Structurally, the film is told as a larger or frame-narrative within which there are three short narratives told in flashback.

All elements of the script work in a harmonious relationship to tell an engaging story.

Anupama Chopra says: “The characters – Veeru, Jai, Gabbar, the Thakur, Basanti and Radha – are familiar in something of the way that Ram and Sita are.

The peripheral players – Soorma Bhopali, the Jailer, Kaalia and Sambha – are the stuff of folklore.

Even the starring animal, Dhanno the mare, has been immortalised.”

She explains: “As character graphs were plotted, symmetries fell into place without effort.

The entire structure of the film is dominated by doublings, by symmetrical pairs of opposites.

The prime mover of the story is a Thakur (landowner): principled, upright, spotlessly clean, with a clipped style of talking.

His nemesis is a daku (dacoit): amoral, sadistic, dirty and gregarious. There are two friends: one, a flirtatious extrovert, and the other a sardonic introvert.

There are two women: one a colourful, uninhibited, jabbering chhamak chhalo (belle), and the other a silent lady of the lamps”.

- DR ANURAG SUBRAMANI is a writer and historian. He is the author of the book, The Fiji Times at 150: Imagining the Fijian Nation (Or, A Scrapbook of Fiji’s History).