In the years following his campaign across the Yasayasa Moala and the so-called “valu ni lotu”, Enele Ma’afu’s influence in Fiji grew stronger, his strategies increasingly shrewd, and his ambitions unmistakable.

The Tongan prince, turned-chief, had firmly entrenched himself in Lau, but by the mid-1850s, his reach extended deep into Vanua Levu and beyond, sometimes through diplomacy, often through war.

This fourth instalment of our continuing series on Ma’afu reveals a man navigating a complex political terrain.

One that was defined by competing Fijian chiefs, religious conversion, and the growing attention of imperial powers.

One prince, two kingdoms

While Ma’afu was officially governor of the Tongans in Fiji under King George Tupou I, the lines between his allegiance to Tonga and his aspirations in Fiji grew increasingly blurred.

Tupou’s own public reflections hint at a deeper trust and perhaps an expectation that Ma’afu could one day inherit the Tongan crown.

But Ma’afu’s appointment in Fiji, under the watchful eye of the British, increasingly ruled out that succession.

Instead, Ma’afu leaned into his influence in Fiji.

His governance of the Tongan settlers in Lau gained praise, even from critical missionaries.

John Polglase, a Wesleyan missionary often wary of Tongan misconduct, credited Ma’afu with imposing order and restraint on his own people, remarking that his “mind was being awakened to the responsibility of his position.”

Instability in the North

Ma’afu’s influence became decisive in Bua and Macuata, where he was drawn into escalating local conflicts.

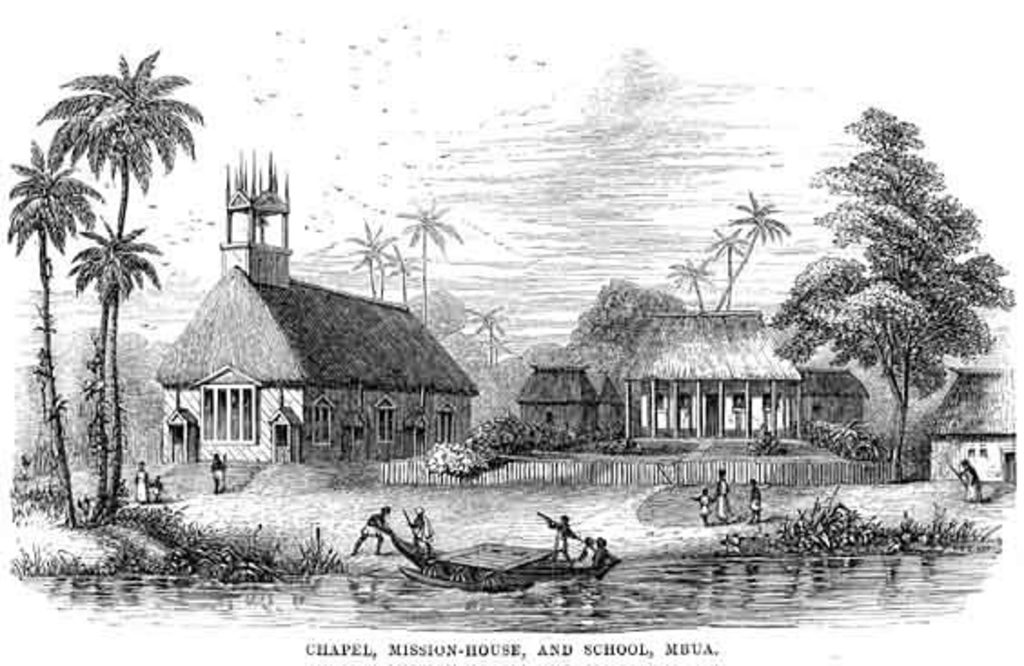

The region was a powder keg, where religious rivalries, inter-chiefdom vendettas, and external missionaries (both Catholic and Wesleyan) stoked factional fires.

When the Christian Tui Bua called on Ma’afu for help against the “heathen” forces of Ritova and his allies, including the ever-defiant Ratu Kapaiwai Mara, Ma’afu responded with military force.

The campaign, though couched in the language of religious righteousness, was far more political than spiritual. Villages were razed, prisoners taken, and strategic alliances reshaped.

In one act that underlined both military cunning and political calculation, Ma’afu lured Tui Wainunu aboard his canoe under a pretext of peace, only to take him prisoner.

This “Tongan war,” as it came to be known in Bua, culminated in a symbolic soro to Ma’afu and Tui Bua with baskets of earth and tabua.

Not only had Ma’afu extinguished Bauan influence in the region, but he had also stamped Tongan authority on much of northern Fiji.

In the shadow of empire

While war raged in the north, another theatre of influence was unfolding in the capital.

The American indemnity claim of $45,000 in damages owed by Cakobau to US citizens had placed unbearable pressure on the Vunivalu of Bau.

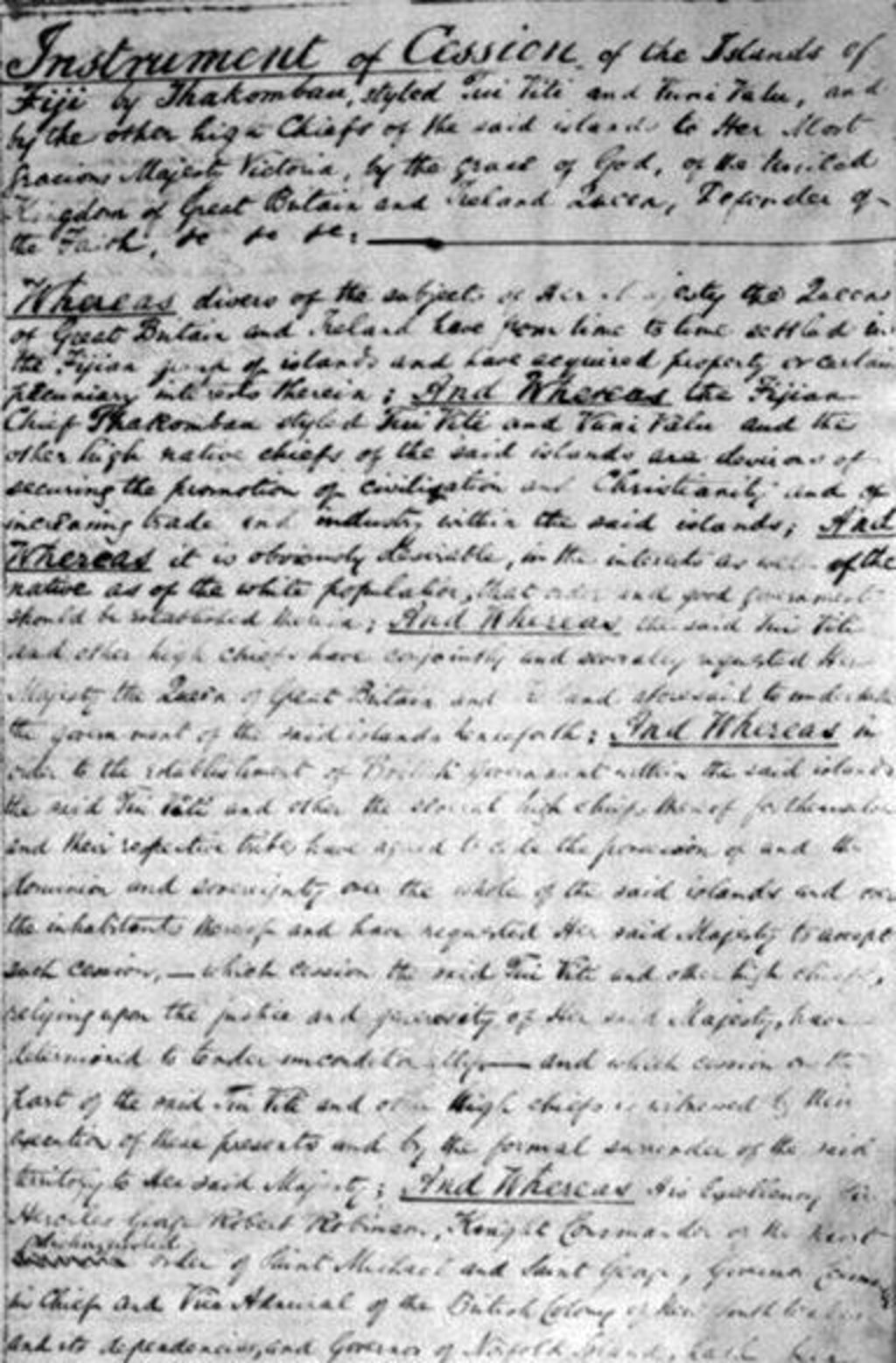

Unable to pay and facing humiliation, Cakobau turned to Britain, offering to cede Fiji in exchange for protection.

This moment of desperation played perfectly into Ma’afu’s hands.

Despite not being among the original signatories to the Deed of Cession, Ma’afu became its chief proponent.

When leading chiefs wavered, he persuaded them to sign which underlined his own pragmatism.

If the British were to come, better they arrive under favourable terms, with Ma’afu already a dominant power.

And dominate he did.

With Bau weakened and Ratu Mara hanged, Ma’afu consolidated influence over Vanua Levu and Taveuni.

He divided Macuata, placing loyal chiefs under tribute.

In a masterstroke, he installed Tui Cakau as “King of all Vanua Levu and the Windward Islands”, a move that simultaneously elevated a lotu rally and reinforced Ma’afu’s indirect rule.

A calculated statesman

By 1859, Ma’afu’s reputation among Europeans and Fijians alike was paradoxical.

To missionaries, he was both a Christian patron and an enabler of violent conquest.

To European consuls, he was a “sovereign” in all but name.

To his Fijian allies, he was a protector.

And to his rivals, he was the single greatest threat to their autonomy.

A pivotal moment came when Ma’afu arrived at Bau with hundreds of armed men, not to fight, but to mediate internal conflicts among Cakobau’s kin.

Together, they examined rebel chiefs and passed sentence.

This was not just peacemaking, it was a kind of statesmanship.

But his motives were questioned.

Was he positioning himself as the stabiliser of Fiji to gain British favour? Was he preparing the ground for future conquest under the cloak of diplomacy?

Consul John Williams’s assessment was blunt.

“A powerful chief of great influence, for instance the Tongan chief of the Windward Isles,” could, through war and diplomacy, become ruler by right.

In 1859, that man was undeniably Ma’afu.

Pathway to Bau

With Solevu under control, Ritova imprisoned, and Cakobau’s power waning, Ma’afu’s eyes turned squarely toward Bau.

He may not have declared it openly, but his intentions were clear.

As one contemporary put it, “The road to Bau now lay open before him.”

If Ma’afu’s earlier campaigns were about consolidating Tongans in Lau, his current efforts were focused on absorbing the and presenting himself as the inevitable successor, not just in influence, but in legitimacy.

In the next instalment, we will explore how Ma’afu’s ambitions clashed with the slow, reluctant advances of the British empire, and how his final transformation, from foreign invader to accepted Fijian chief, was sealed.

n This article was compiled using historical insights from John Spurway’s book titled Ma`afu, prince of Tonga, chief of Fiji: The life and times of Fiji’s first Tui Lau.

A copy of the 1858 Deed of Cession offered to Britain—Ma’afu played a key role behind the scenes. Picture: SUPPLIED

Sketch of a mission house and chapel on Bau – Wesleyan missions played a complex role in Ma’afu’s consolidation of power. Picture: SUPPLIED