Earlier this month, Fijians witnessed the formal installation of Ratu Tevita Lutunauga Kapaiwai Uluilakeba Mara as the paramount chief of the Lau group of islands.

Widely known as Roko Ului, Ratu Tevita is the only surviving son of Fiji’s founding prime minister, the late Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara.

With his installation, he now assumes the revered titles of Tui Nayau, Sau ni Vanua ko Lau, and Tui Lau — all once held by his father.

The Tui Nayau and Sau ni Vanua ko Lau titles trace back to Fiji’s tribal past, deeply entrenched in the chiefly structure of the Lau archipelago.

The title Tui Lau, however, is a more recent addition to Fijian chieftaincy and was born out of a unique period in the region’s political and cultural evolution.

The first to hold the Tui Lau title was Enele Ma’afu, a formidable Tongan nobleman whose arrival in Lau in the 19th century marked a turning point in the region’s history. Ma’afu’s leadership laid the groundwork for a hybrid chiefly system, which merged Tongan governance traditions with those of Lau.

His influence was profound, setting in motion a lineage that would later include revered figures such as Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, and now, Ratu Tevita.

Today, Lau is a confluence of two great Pacific cultures , Fijian and Tongan, and at the heart of this cultural synthesis is the enduring influence of the first Tui Lau, Enele Ma’afu.

The unyielding chief

Henry Britton, a correspondent for the Melbourne Argus, witnessed a scene of remarkable order amidst the burgeoning chaos of pre-colonial Fiji.

At the annual assembly of the Lauan chieftains on Lakeba, one figure dominated, his name was Enele Ma’afu, the Tui Lau.

“He looks every inch a chief,” Britton wrote, struck by Ma’afu’s imposing six-foot frame, resolute face, and commanding presence, clad in a black frock coat and patent-leather boots.

This image, captured in John Spurway’s meticulously researched biography, Ma’afu, prince of Tonga, chief of Fiji, encapsulates a pivotal moment.

Ma’afu, the Tongan prince who became one Fiji’s most powerful chiefs, stood at the centre of a desperate struggle for control as European powers circled and rival Fijian chiefs vied for supremacy.

Spurway’s work reveals Ma’afu not as a mere footnote in Fiji’s path to British annexation in 1874, but as the architect of arguably the most sophisticated indigenous governance system in the archipelago during the turbulent 1860s and early 1870s.

His recognition as Tui Lau in 1869 formalised his separation from Tonga and positioned his rivalry with Bau’s Vunivalu, Ratu Cakobau, on a new, more dangerous stage.

As Spurway detailed, with Fiji’s European population growing and demands for protection escalating from colonial governments in Australia and beyond, Ma’afu’s consolidation of power in the Lau group brought the question of his ultimate ambition into sharp focus.

The Lauan state – a model for peace

While Levuka, Fiji’s embryonic capital, buzzed with settler intrigue, rumour, and political vacuum, Ma’afu’s Lau presented a stark contrast.

Spurway meticulously reconstructed the “Lauan Constitution” formulated in 1869 and refined in subsequent Assemblies.

This was no mere symbolic document. Under Ma’afu’s firm hand, Lau boasted uniform laws, a functioning bureaucracy recording births, marriages, and deaths, uniformed police, and, crucially, a sophisticated land and taxation system that underpinned its stability.

Ma’afu’s land reforms, adapting Tongan practices to Fijian contexts, were revolutionary and controversial.

The magimagi system involved measuring coastal allotments inland, granting landholders fishing rights, cultivable land, and bush reserves.

Crucially, Spurway emphasised Ma’afu’s assertion of paramount control.

“After the lands are apportioned out to the native taxpayers, the residue shall be considered as government lands, and the head of the Chiefdom shall have sole control thereof.”

He leased large tracts, primarily to European planters on Vanuabalavu and other islands, for 50-year terms, generating significant revenue.

Yet, as Spurway documented through later Land Commission evidence, this often came at the expense of the taukei (traditional landowners), who were frequently dispossessed without consultation or share of rents, leading to lasting grievances despite the system’s administrative efficiency.

Stipendiary Magistrate Charles Swayne, years later, acknowledged the enduring power of Ma’afu’s allocations.

“Boundaries operative during Ma’afu’s time were recognised…No magimagi established by Ma’afu could be the subject of any dispute.”

Taxation was equally rigorous.

Every male over 16 paid 15 gallons of coconut oil (later increased) or its cash equivalent; women paid 3 shillings or equivalent in goods.

“Ma’afu lacked nothing in devising new sources of revenue,” Spurway noted, even taxing trainee missionaries, much to their superintendent’s dismay.

This system, while burdensome, funded administration and Ma’afu’s ambitions, allowing him to indulge in symbols of power like the sleek racing yacht Xarifa, purchased for £1,000 – a staggering sum indicative of Lau’s relative wealth.

The rivalry intensifies

Cakobau, ensconced at Bau and heavily influenced by European advisors, viewed Ma’afu’s growing power with profound unease.

Spurway chronicled their complex dance of rivalry and uneasy cooperation.

They jointly signed petitions to Britain seeking a protectorate — Cakobau hoping for security against American debt claims and Ma’afu perhaps seeking international recognition or simply playing for time.

Yet, distrust ran deep.

Cakobau accused Ma’afu of plotting his downfall, complaining bitterly to consuls and settlers about Ma’afu’s “treachery” and attempts to arm groups like the Lovoni people of Ovalau against Bauan allies — accusations substantiated during the Lovoni rebels’ treason trial in 1871.

Missionary Lorimer Fison, a keen observer quoted extensively by Spurway, provided a damning analysis of Cakobau’s position.

He dismissed the notion of Cakobau as “King of Fiji” as “false in fact… unjust in law [and] most disastrous in its consequences,” arguing that only Ma’afu possessed the power and vision to prevent widespread violence in the post-Cakobau era.

The settler press reflected this perception; the Fiji Times acknowledged Ma’afu collected the largest revenue, offered effective protection, and was the “one man” preventing Cakobau’s complete dominance.

The Cakobau government

The chaotic political landscape culminated in the formation of the Cakobau government in June 1871.

Spurway dissected the intrigue behind this “coup d’état,” orchestrated largely by Europeans like Sydney Burt.

Facing settler demands for order and land security, and needing chiefly legitimacy, the plotters secured Cakobau as a constitutional monarch. The masterstroke, however, was persuading Ma’afu to participate.

In a dramatic Levuka meeting in July 1871, brokered partly by trader William Hennings (to whom Ma’afu was deeply indebted), the rivals apparently settled their feud.

Cakobau was acknowledged as King; Ma’afu became Viceroy and Commander-in-Chief of Lau, receiving £1,000, a salary of £800, and clear title to the Yasayasa Moala.

Spurway highlighted the scepticism surrounding this “rapprochement.”

Consul Edward March believed Ma’afu accepted only because he was “flattered with the hope of eventually succeeding to the throne of Fiji.”

Hawaiian envoy Charles St Julian, meeting Ma’afu soon after, reported the Viceroy’s private doubts about the government’s viability but noted his shrewd calculation, which was centred on securing his Lauan base while positioning himself to “watch events and act as circumstances may require.”

Ma’afu’s subsequent admonition to the new government over Cakobau’s interference in Bua affairs and warning that it threatened the very foundation of unity, revealed his continued assertion of independent authority under the vice-regal cloak.

“He looks every inch a chief”

John Spurway’s Ma’afu, prince of Tonga, chief of Fiji paints a compelling portrait of this pivotal figure.

Ma’afu was no unblemished hero.

His land policies caused hardship, his ambition fuelled conflict, and his involvement in the Lovoni rebellion was cynical.

Yet, his achievement in forging the Lauan state is a living monument to his political acumen and administrative skill, creating an “oasis of order” (as termed by observers) in a fragmenting Fiji.

When Britton declared he “looks every inch a chief,” he was referring to more than Ma’afu’s physical presence.

He recognised the aura of authority, the strategic mind, and the sheer force of will that made this Tongan prince one of the most formidable chiefs in Fijian history, whose manoeuvrings shaped the islands’ destiny long before the British flag was raised.

His legacy, enshrined in the enduring magimagi boundaries and the very structure of Lau, underscores his profound impact on Fijian history.

This article was compiled using historical insights from John Spurway’s book titled “Ma`afu, prince of Tonga, chief of Fiji: The life and times of Fiji’s first Tui Lau.”

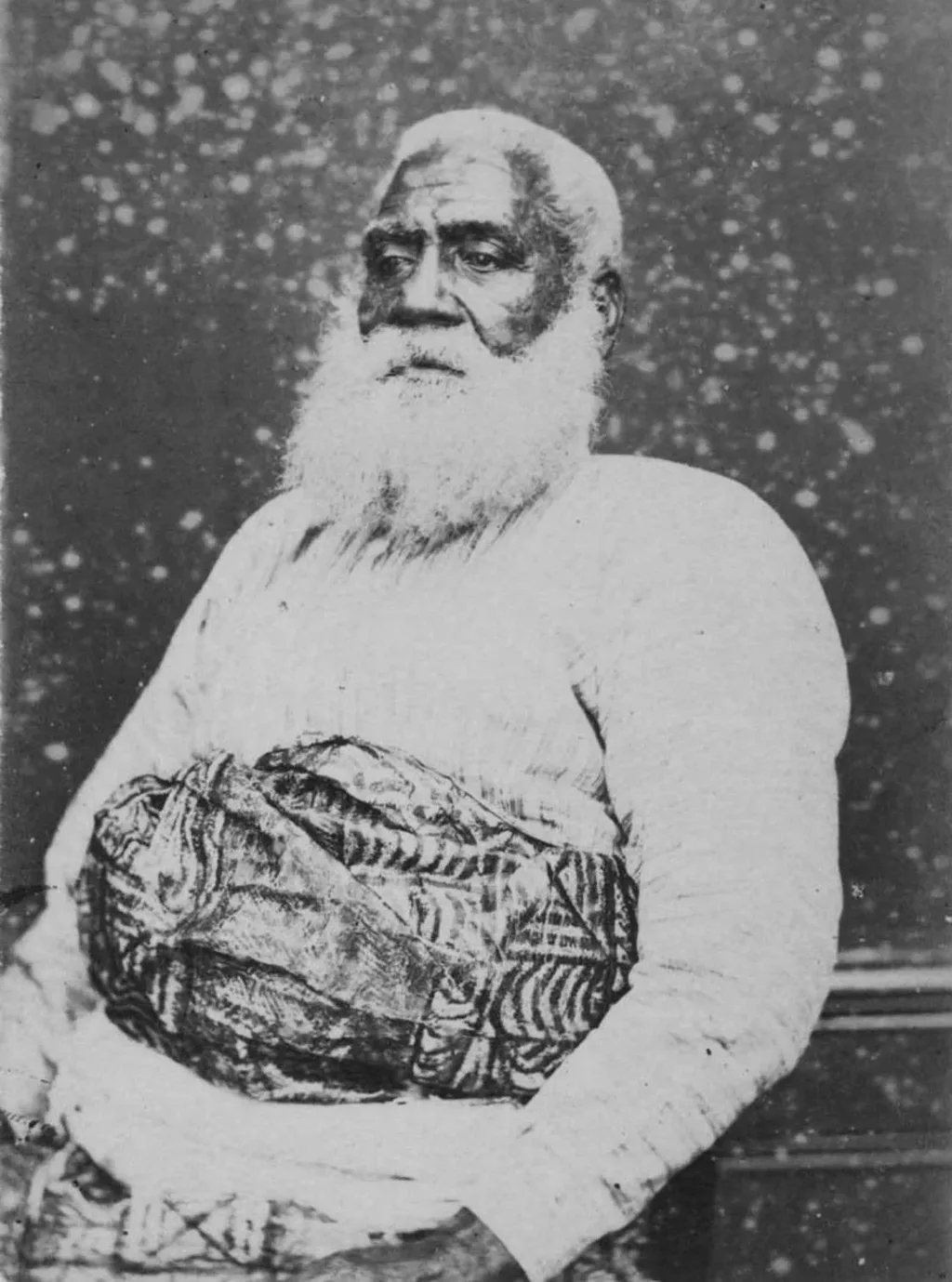

Vunivalu of Bau and Ma’afu’s greatest rival, Ratu Epenisa Seru Cakobau. Picture:

SUPPLIED

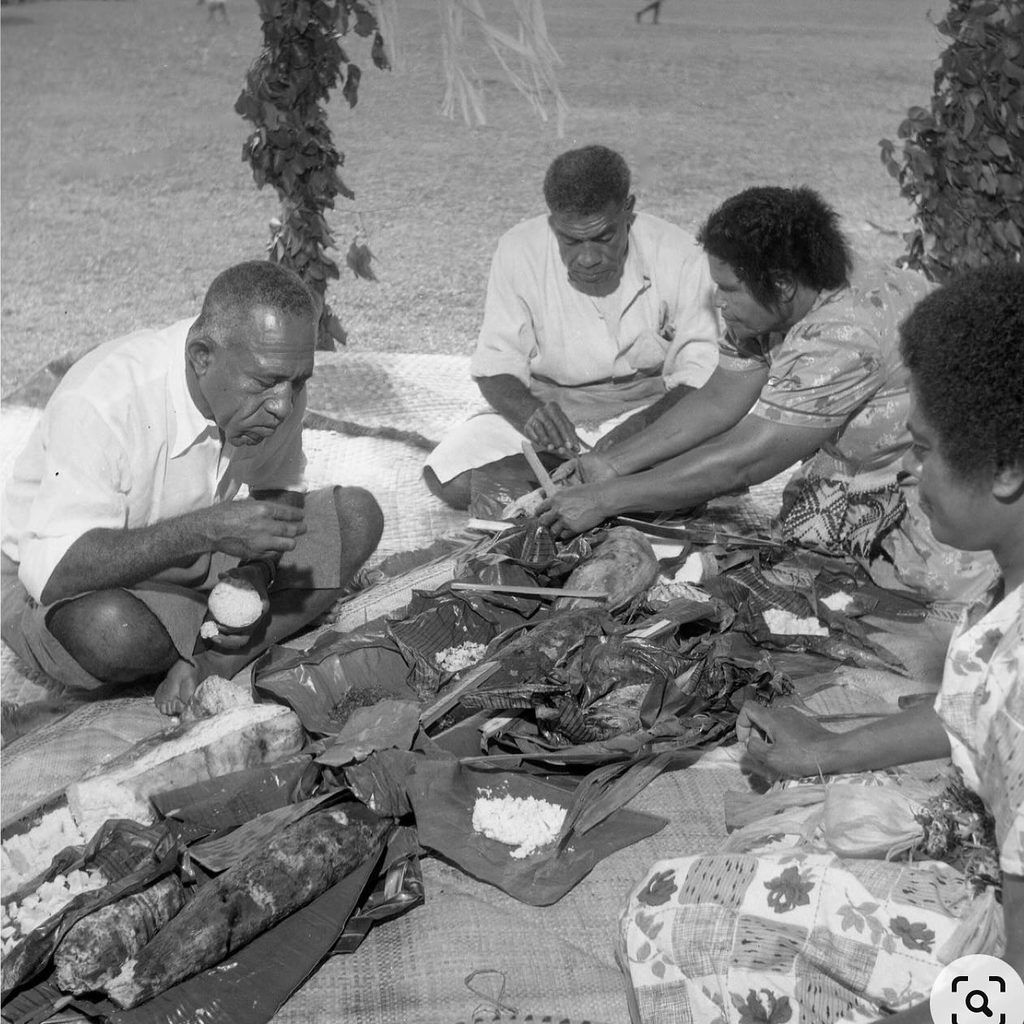

Roko Tui Bau Dr. Ratu J.A.R Dovi (left) enjoys a feast with Tui Nayau Ratu Tevita Uluilakeba at Lakeba in 1956.

Picture: NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF FIJI