Last month, The Sunday Times explored the history of the Methodist Church in Fiji and Rotuma’s path to full autonomy in 1964 in an article titled ‘The Yearn for Independence.’

Today, we delve deeper into the decades-long struggle that shaped the church’s identity away from colonial oversight towards self-governance and the key figures who championed this historic transition.

The push for a new

constitution

The Methodist Church, like any enduring institution, is guided by doctrine—principles that define its mission and values. For Fiji’s methodist community, the journey toward independence was a gradual but determined process, spanning two decades (1943–1963) and culminating in the formation of a constitution that would solidify its autonomy.

However, the seeds of this movement were sown much earlier. Even before the chaos of World War II in 1945, indigenous (iTaukei) methodist ministers had been advocating for a new constitution, one that would not only grant the church independence from the Methodist Church of Australasia but also modernise its doctrines to address Fiji’s evolving socio-economic and cultural landscape.

The late Reverend Allan Tippett, a minister serving in Fiji at the time, was a vocal supporter of this cause. He recognised that the church needed to adapt to the challenges brought on by colonialism, the arrival of indentured labourers from British India, and the influence of foreign settlers, all of which were reshaping iTaukei society.

Laying the foundation

Historical records indicate that discussions about reforming the Methodist Church’s constitution began as early as the late 19th century. Reverend Tippett once remarked that the Methodist Church in Fiji was the strongest and most disciplined in the Pacific, a testament to its deep roots in Fijian society.

Before independence, every decision made during the church’s annual meetings had to be sent to the Methodist Board of Mission in Australia for approval.

These discussions encompassed a wide range of issues like previous meeting agendas, future plans, rituals, financial matters, and theological doctrines, all of which would eventually form the backbone of the church’s constitution.

The transition from a mission-focused church to a fully institutionalised body was gradual. Much of its strength came from the early unification of church missions under the Wesleyan movement, led by pioneering figures like Reverends William Cross, David Cargill, John Hunt, James Calvert, and Thomas Jagger. Their work laid the groundwork for a structured set of principles, doctrines, and laws that would guide the church for generations.

The fight for iTaukei inclusion

One of the most significant hurdles in the church’s journey was the exclusion of iTaukei ministers from leadership roles. For years, indigenous ministers faced discrimination from their European counterparts, despite their crucial role in spreading the gospel.

The late Reverend Joseph Waterhouse was among the first to challenge this status quo. He argued that iTaukei ministers were not only essential to the church’s mission but also divinely gifted in their service. He pushed for their official recognition during annual synods, insisting they be given the right to speak and vote on church matters.

Over time, more European ministers began acknowledging the dedication of their iTaukei colleagues, advocating for equal privileges. The case was made that Indigenous ministers needed to be part of key meetings to fully understand church regulations, financial management, and doctrinal principles—skills vital for leadership.

Reforms take shape

By the early 1900s, major constitutional reforms were underway. In 1901, Reverend George Brown, general secretary of the Methodist Church of Australasia, approved sweeping changes. Among the most significant was the inclusion of iTaukei ministers in all major church meetings, ministerial gatherings, the Bose ko Viti (Fiji Conference), and financial discussions.

Crucially, the reforms also opened church assemblies to all congregants, regardless of race. Leading this transformation was Reverend Arthur J. Small, then-head of the Methodist Church in Fiji and Rotuma. By 1902, iTaukei ministers were, for the first time, granted leadership positions.

Opposition and tensions

Not everyone welcomed these changes. In 1907, a delegation from the Methodist Board of Mission visited Fiji to assess the church’s progress. They concluded that the new laws were well-structured to address societal changes.

However, some European clergy members resisted, fearing that an independent Fijian church would diminish their influence. Threats were made to leave Fiji entirely if their concerns were ignored. This brewing conflict would soon reach a tipping point.

However, the early visionaries like Reverends Tippett and Waterhouse to the reformers like Reverend Small, each played a pivotal role in shaping a church that truly reflected the people it served.

The Methodist Church in Fiji did not simply inherit its independence, it earned it.

Former President of the MCIF Reverend Ili Vunisuwai. Picture: MCIF/FACBOOK

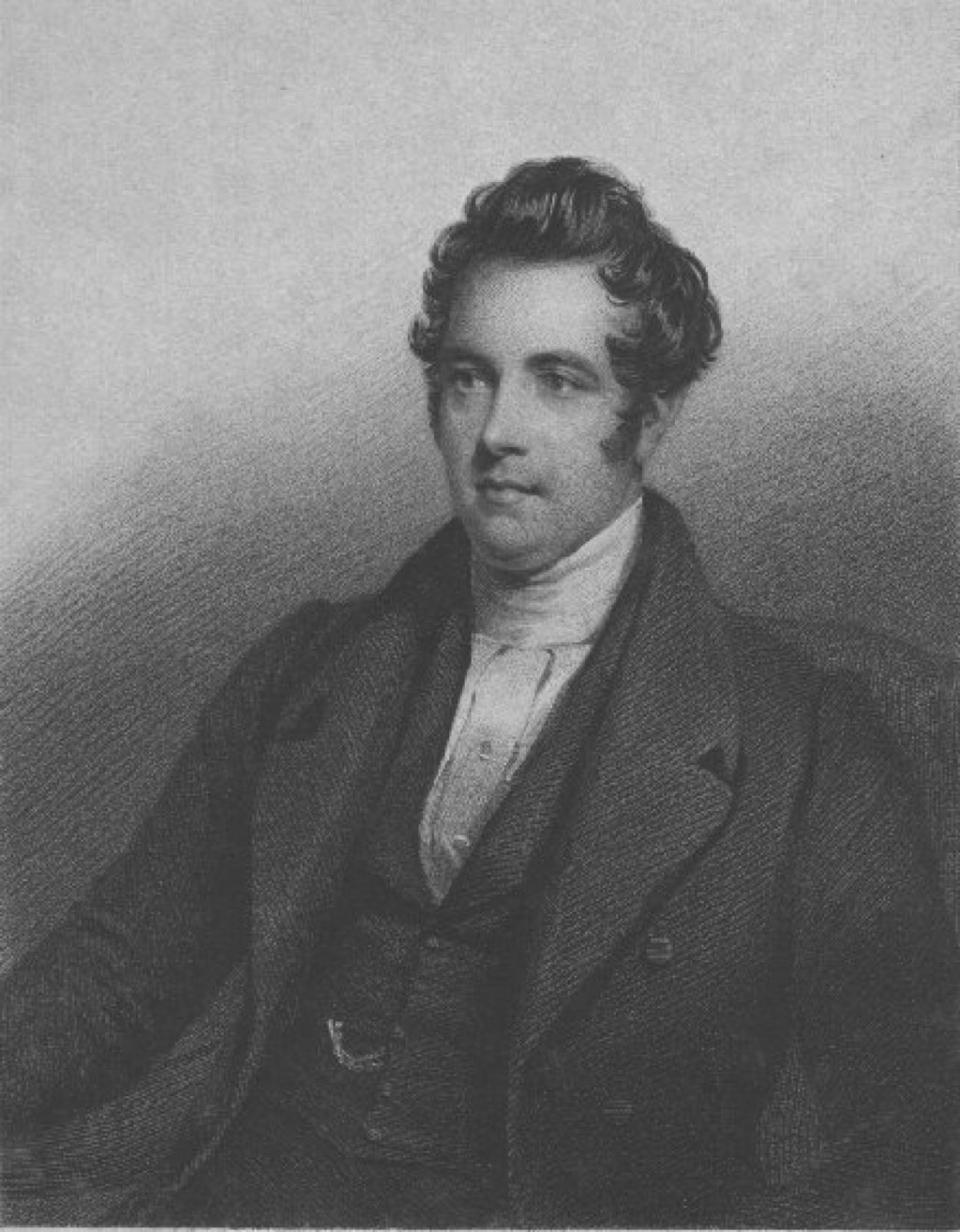

Missionary and linguist, the late Reverend David Cargill. Picture: FT FILE

The Methodist Church is still the largest Christian denomination in Fiji and influential in every sphere of society. Picture: FACEBOOK