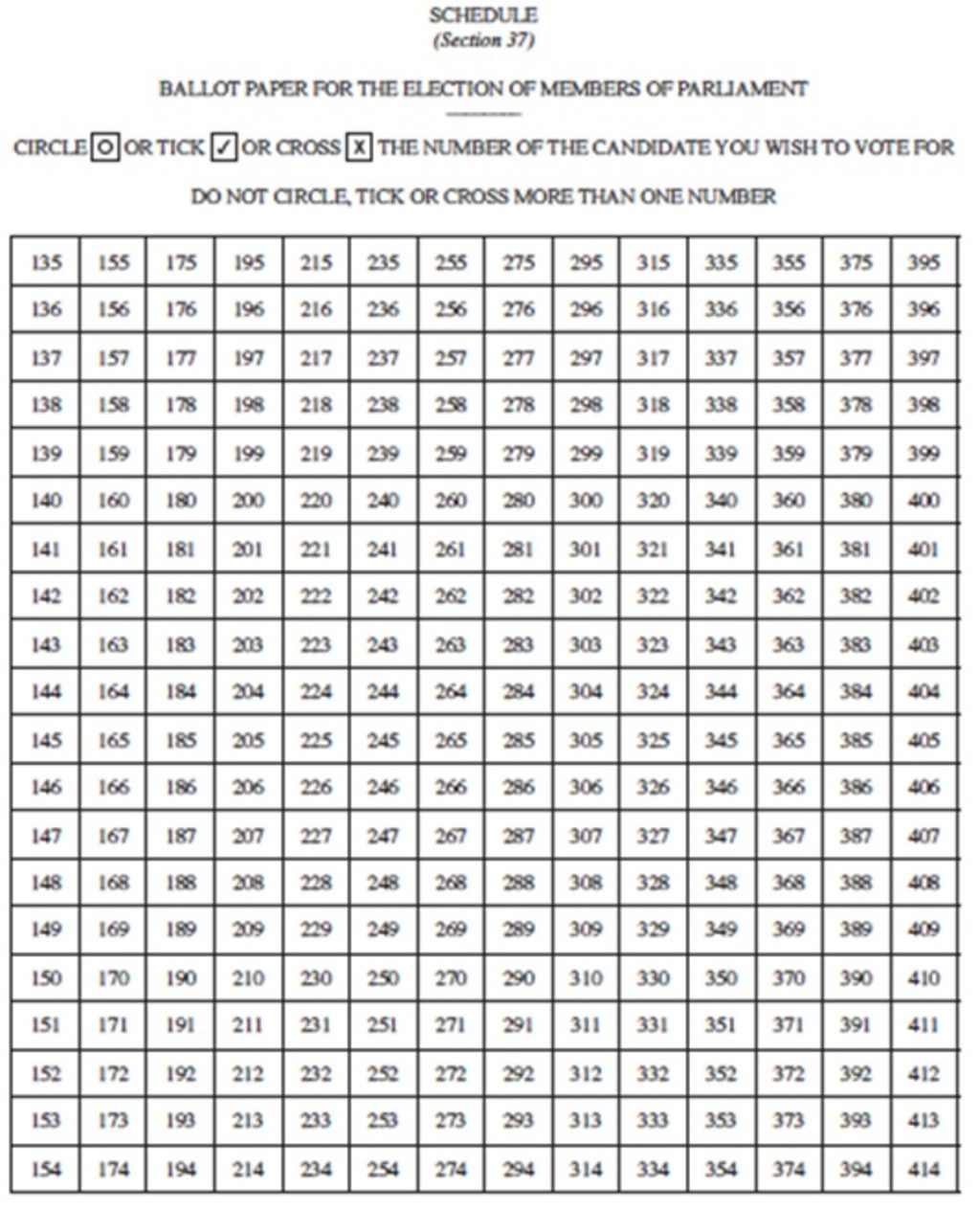

Fiiji’s current electoral system has been criticised on numerous grounds: the confusing Sudoku ballot paper which features only numbers, without names or party symbols; the ‘big man’ or ‘rock star’ syndrome which makes party fortunes determined by having a popular leader with nationwide appeal; the fact that some MPs can get elected with less votes than candidates who fail to get elected; the single national constituency of 55-members which ensures that MPs do not represent any specific geographical area within Fiji; the 5 per cent nationwide threshold which discriminates against small parties and independent candidates; and the low number of women elected.

Less often mentioned are its positive aspects – above all, the shift to proportional representation, the move away from the out-dated racially-reserved seats, getting rid of the former bias against urban voters and the reduction in the voting age from 21 to 18. The earlier system, the alternative vote, was a classic case of well-meaning electoral engineering that went badly wrong.

In this lecture, I will firstly argue that the timing is wrong for electoral reform right now. We are too close to a general election. Secondly, the Supreme Court will soon deliberate on the status of the 2013 Constitution. Presently, the 2013 Constitution including its electoral provisions, can only be amended if there is a 75 per cent parliamentary majority followed by a 75 per cent majority of all registered voters in a referendum. That is an absurdly high threshold for a Constitution that was not assembled by any elected authority and was not itself put to any referendum.

If the Supreme Court were to strike down those amendment provisions, that would open the door to post-election deliberation about both constitutional and electoral reform. If that happens, Fiji would be best advised to retain a proportional representation system of one or other type and not to revert to a ‘winner takes all’ majoritarian system.

What is the electoral system?

Narrowly defined, the ‘electoral system’ refers solely to ballot paper design, district size and the formula used for converting votes cast into seats won. If we disregard direct democracy methods like hand counts, all modern electoral systems have those three aspects. But commentators in Fiji (& elsewhere) often refer to electoral reform in a broader sense, including all the administrative rules surrounding elections, political parties and candidates. Some go even further and include also the format of parliament (whether to have an upper house or senate) or how to constitute a cabinet (whether to endorse power-sharing rules). Many of those questions are interlinked. But, for the purpose of this lecture, which focuses both on electoral reform and constitutional change, I intend to use the term electoral reform in its narrower sense.

Amending Open List Proportional Representation (OLPR)

I have argued that there exists more scope for a major revision of Fiji’s OLPR system within the confines of the 2013 Constitution than is commonly recognised. Section 53 (1) of the 2013 Constitution provides that ‘The election of members of Parliament is by a multi-member open list system of proportional representation, under which each voter has one vote, with each vote being of equal value, in a single national electoral roll comprising all the registered voters’. Within the 2013 Constitution, then, one cannot go back to single member districts of the type provided under the 1970 and 1997 constitutions. Constituencies must be multi-member and they must use the open list formula which, by definition, gives eligible voters some choice of candidates as well as parties. What has been widely misinterpreted is the last phrase ‘in a single national electoral roll’. This is commonly thought to specify a single national constituency of the type used in 2014, 2018 and 2022. That is reading history backwards. In fact, it refers to the discontinuation of the use of communal rolls. It is perfectly possible to have multiple districts with a single national roll or register. Most countries have a single register, but multiple constituencies.

Fortunately, the debate has now moved on from one about whether the single national district is required by law to one about whether or not it is desirable. Dialogue Fiji and the University of Fiji have argued that a single nationwide constituency is the best way to preserve the ‘one person, one vote, one value’ principle, another of Bainimarama’s non-negotiable provisions ahead of the 2013 Constitution. But the way that operates is influenced by the 5 per cent threshold. A vote for a candidate or party that falls below the 5 per cent threshold is not of equal value to one that surpasses that threshold. Many countries around the world have laws that require equality in district size (e.g. the United States, which uses a first-past-the-post system with 435 congressional districts). Other countries put more emphasis on ‘communities of interest’ and allow more remote places (such as outer islands) to have smaller districts. In Fiji, the earlier systems under the 1970, 1990 and 1997 constitutions were skewed in favour of rural parts of the country, and the small islands. The urban areas were gravely under-represented. The change in electoral law has addressed that issue. Equality of votes is a valuable principle, but it is not the only important issue in electoral law.

All electoral systems balance representation and accountability. Big districts allow highly proportional outcomes, meaning that party seat shares can become very close to party vote shares. Smaller districts allow greater accountability, bringing representatives closer to their voters. Political scientists John Carey and Simon Hix find what they call an ‘electoral sweet spot’ in ‘low district magnitude proportional representation’ systems because these offer reasonably proportional outcomes while keeping close links between MPs and their constituents (American Journal of Political Science 2011).

There is another strong reason for favouring a shift to a multiple district open list system. Many of the major defects of Fiji’s present system would be addressed if Fiji moved to a three-four or even ten district arrangement. The present soduku ballot paper shows only numbers, not even candidate names. It does not show parties, but the ballots are all counted by party initially. Only after it is established how many seats each party secures do the tallies within parties determine which individuals get seats. Under OLPR systems, it is the party that is critical. To have a ballot paper that features only candidate numbers gives the voter the false impression that the parties do not matter much.

The presently used ballot paper is confusing for the voter. It may not generate high invalid vote shares, but it does encourage large numbers of erroneous ballots. Frank Bainimarama personally obtained 40 per cent of the nationwide vote in 2014, and his allotted number was 279. The much less well-known politician who was allocated the similar number 297, secured 4932 votes, an unexpectedly large tally for a little-known candidate. Clearly, many were confused about the numbers. In 2014, that fortunate candidate’s party did not reach the 5 per cent threshold, so the confusion did not result in the election of that particular candidate. In 2018, Bainimarama’s number was 668. At that election, one candidate was elected on the basis of voters having mixed up the numbers 668 and 688. He was one of the four top-20 FijiFirst vote recipients. Fortunately, that 668 candidate was from the same party as Bainimarama. That will not always be the case. There is a major risk that erroneous voting may, at some point in the future, decide the composition of government. In December 2022, Fiji witnessed a Prime Ministerial election where one vote decided the outcome. Imagine the outcry if that one MP had been elected on the basis of erroneous ballots.

In a multiple constituency framework, a more voter friendly ballot paper would be feasible. It would become possible to list the candidates under the parties. Another advantage of such a reform is the effect on the 5 per cent threshold. In a nationwide constituency, that threshold is fairly high. It discourages small parties or independent candidates. In a multi-district model, 5 per cent is not too high a threshold. Small parties and independents would stand a much greater chance of victory.

A multi-district system would also diminish the importance of what has been called the ‘rock star’ or ‘big man’ phenomenon. Under the current system, party fortunes depend greatly on having a high profile national leader able to gather a big chunk of the country’s votes. Lesser known candidates are then elected on the basis of that leader’s vote share. That, in turn, leads to protests that some candidates are being elected despite having less votes than others who fail to secure election. Some protest that this too is another violation of the ‘one vote, one value’ principle. The optics are bad. Electoral specialists will rightly respond that this is an inevitable feature of all open list PR systems. It is a byproduct of the fact that the party is the pivotal entity in such systems. But this problem becomes more acute in systems where the party is not plainly visible on the ballot paper. In a multi-district model, no one candidate would be able to secure votes across all districts. Therefore, fewer MPs could rely on securing election on the coat-tails of a high profile national leader.

Electoral law under an amendable Constitution

If the Supreme Court were to open the door to constitutional amendment, what would be the best alternatives? Above all, Fiji should avoid moving back to a single member-based system, such as first-past-the-post (FPTP – 1970-1987) or the alternative vote (AV – 1997-2006). Most political scientists think that proportional representation systems are better suited for countries where ethnic parties are likely to emerge. Fiji’s history gives a clear indication of the problems with ‘winner takes all’ majoritarian systems like FPTP or AV. Single member district systems are inherently majoritarian. If there is only one vacancy to fill, there cannot be a proportional outcome. FPTP encouraged ethnic Fijians and Fiji Indians to back big rival ethnic parties. Any splits in the ethnic vote meant a triumph for the other side. In April 1977, the indigenous Fijian vote split, and a more homogenous Fiji Indian-backed party won. That generated a constitutional crisis. In September 1977, the Fiji Indian vote split between ‘dove’ and ‘flower’ factions. As a result, the predominantly indigenous-backed Alliance gained a big majority. Under FPTP, emergence of splinter parties or small variations in turnout could determine the outcome in marginal constituencies. Even under AV, which some hoped would create robust inter-ethnic coalitions, the ability of parties to control ballot transfers generated vast inequities and highly disproportionate results.

Closed list PR

Open list PR is not the only type of proportional representation. In closed list PR systems, there is no choice of specific candidate. The party controls which candidates get elected. If a party gets 50 per cent of the nationwide vote, it will get close to half the MPs, or even more if smaller parties fail to reach a threshold. Closed list PR systems make it easier to introduce effective quotas to advance women’s representation. In New Caledonia and French Polynesia, closed list systems exist alongside ‘zipper’ rules that require parties to alternate men and women on their lists. As a result, both of these territories have close to 50 per cent women in their legislatures. But closed list PR systems are often criticized for giving too much power to party bosses.

Single transferable vote

The least party-centred proportional electoral law is the single transferable vote system, which was recommended by the Street Commission in Fiji back in 1975. It is similar to AV but used in multi-member districts. Eligible voters may, or sometimes must, rank candidates in order of preference. It is used in Ireland and Malta as well as for the upper house in Australia. It is a fairly complex system, particularly where listing preferences is compulsory. After Fiji’s negative experience with AV in 1999, 2001 and 2006, there is little enthusiasm for shifting to another system with a complex ballot paper.

Mixed member proportional representation (MMP)

Another option that allows some single member districts while preserving nationwide proportionality is MMP, as used in New Zealand, Germany and Lesotho. In MMP systems, a certain share of the seats (usually around half) are elected from single-member districts. The remainder are so-called ‘top up’ seats that ensure something close to nationwide proportionality. These MMP systems have the advantage of delivering an element of local representation as well as proportionality across the country. They also allow parties to secure the election of highly qualified candidates with a national standing who may not fare well in contests for single-member constituencies. The top up seats are usually selected using a closed list formula, as in New Zealand.

Danger of unforeseen

repercussions

In the formulation of electoral laws, small tweaks can have major negative ramifications. For example, when Fiji introduced the highly confusing split format above/below-the-line ballot paper used in the 1999, 2001, 2006 elections, few anticipated that it would allow the parties control over the movement of 92-95 per cent of the ballot transfers. Parties were more strategic than voters. In New Zealand, citizens have two votes under MMP, one in a single-member constituency and the other for a national list. This gives big parties some incentives to encourage like-minded small parties to contest in specific constituencies, while retaining the list vote for themselves. That way, they get an extra allied MP but the big party still gets its proportion of seats. They thereby maximize their strength in parliament but at the cost of violating the proportionality principle. In Fiji, MMP would work better with a single vote rather than two votes.

Horses and carts

To change Fiji’s electoral system at this point would be unwise. The country is too close to the next general election. Changes to the Electoral Act need to be carefully deliberated through parliament. Ahead of an election, parties understandably jockey for influence. Many will be fearful of losing their seats. Coalitions may be reconfigured. It is a poor time to reach cross-party consensus, particularly in the aftermath of the convulsions that followed the de-registration of FijiFirst. The passage of any amendment through parliament takes time. If passed more urgently, using Standing Order 51, that would be tailor-made to maximize opposition suspicions that the government is seeking to implement reforms to its advantage. Electoral reform is best done on a bipartisan (or multi-partisan) basis, with parties jointly agreeing changes to the rules.

If the Supreme Court were to uphold the unamendable 2013 constitution in entirety, the option of a shift to a multi-district open list PR system would go some way towards addressing many of the major defects of the present system. If the doors were open for constitutional amendment, other options – such as MMP, with a single vote, merit consideration as does a shift to a multi-district OLPR system. Fiji should not revert to a majoritarian ‘winner takes all’ system. The country is better off with a proportional representation system of one or other type.

A sample ballot paper used in Fiji’s elections – central to ongoing calls for electoral reform and greater transparency in the voting process.. Picture: SUPPLIED