“You belong to us, not to them!” These were the words of an elderly Catholic woman in Naleba, spoken with genuine concern to a young Fr Frank Hoare, who had been generously accepting lunch invitations from a nearby Muslim family.

Last week, we saw how Fr Hoare’s earliest days in Fiji were filled with unexpected lessons, from yaqona sessions that revealed unspoken questions, to festive meals and playful pranks that revealed the warmth of a new culture.

This week, we follow him into the sugarcane fields of Labasa, where his real missionary life begins, without electricity, without guidance, but with people ready to teach him what it means to truly belong.

Settling In

It was 7 November 1974, and Fr Hoare had just stepped into a new chapter of his missionary journey.

Having completed his Hindi training in Suva, he arrived at Naleba settlement in Labasa – a small village nestled between cane fields and the sea – ready to begin his first full mission posting.

But “ready” is always a relative word.

The priest’s room at the back of the church was basic, stripped to essentials – no electricity, no fridge, no oven, no indoor plumbing.

On the first night, Fr Pat McCaffrey, the local parish priest, had shown him in, shared a brief birthday celebration with a nearby Catholic family, and then promptly left for town, without mentioning what to do for meals.

“I looked out over the darkened cane fields to the distant sea glimmering faintly in the moonlight. A flash of lightning lit up the countryside below.

“This would be the land where my mission would begin.”

The next morning, the knocking came.

“Get up, Father. It is six o’clock!”

Standing outside his door was Gabriel, a young man who was mentally challenged, brimming with urgency, a reminder that in Naleba, even the newest priest had duties to fulfil. There were no leisurely lie-ins on mission.

“After some prayers I made a cup of tea using a kerosene stove and ate some crackers with peanut butter,” Fr Hoare said.

“I then had a look around my room and the church before exploring the surrounding area.

“One of my neighbours was a Muslim family. They called out to me in a friendly way.

“While chatting I discovered that the daughter in the family had cut her foot.

“I got my first aid kit, cleaned the wound and put a plaster on it. Her mother offered me lunch.

“I was glad to accept.”

The next day, the wound dressing needed changing. Again, he was invited for lunch. The kindness was mutual, natural.

But that morning, Gabriel came bearing a message. His grandmother, a matriarch in the Catholic community, had something to say.

“You are supposed to come here… You belong to us.”

A line that carried more than a meal plan, it was about identity, about expectation, about faith lines drawn across shared spaces.

Crossing cultural currents

By March 1975, Fr Hoare was learning the inner texture of Indo-Fijian spirituality.

Lent had arrived, and with it, a depth of devotion he hadn’t quite anticipated, especially being his first.

There was something humbling about it, something fierce and pure.

Teenage girls in the village fasted with a kind of ascetic commitment that startled him – one meatless meal a day, every day for 40 days.

“Our Catholic fasting seemed tame in comparison,” he wrote.

And we are well aware that for Indo-Fijians, music, too, was woven into worship in rich and joyful ways like bhajans, kirtans, naam jap. Fr Hoare saw how the rhythms of praise carried the people closer to God.

Even illness became a gateway to spirituality.

“I have a headache, Father. Can you blow it away?”

The request came from an elderly Muslim woman. Bewildered but gentle, Fr Hoare laid hands on her head and prayed.

It was new ground for him, belief systems blending in ways that were both strange and sacred.

A lesson in leadership

April came with its own trial, not of faith, but of foundations.

“There was, on the compound, only a small wooden church with a priest’s bedroom at the back.

“At least, a place for people to hold meetings, shelter and socialise was needed.

“Plans were made for a simple shed with two walls, concrete floor and galvanized iron roof.

“A carpenter and one paid helper were employed.

“The male Church members would supply voluntary labour.

“A day was agreed for the men to dig the foundations, which had already been measured out by the carpenter.”

But as often happens, the workday began with a trickle, not a flood.

The elders arrived, sat waiting.

Fr Hoare said a few grumbled that others hadn’t shown up. The atmosphere grew thick with hesitation.

Then, the church committee president, a quiet elder, stood up.

No lecture. No fanfare. Just action.

“He removed his jacket, picked up a tool, and began digging.

“The others followed. By lunchtime, the foundation was dug.”

Leadership, Fr Hoare learned, wasn’t about commands. It was about example.

The simple things that stay

There were no grand cathedrals in Naleba, no newspaper clippings or dramatic conversions.

But in these early days, Fr Hoare found the foundation of something deeper, a ministry made from tea and crackers, healing plasters, fasting girls, and quiet elders who led with their hands.

Each encounter, whether filled with laughter or quiet discomfort, helped him see what it truly meant to walk with people, to share in their joys, customs, irritations and beliefs.

This wasn’t just his mission.

It was his formation.

n Next week, in The Fiji Times, we continue with Fr Hoare’s journey into community life in Labasa where more lessons of spirit, culture, and humour await.

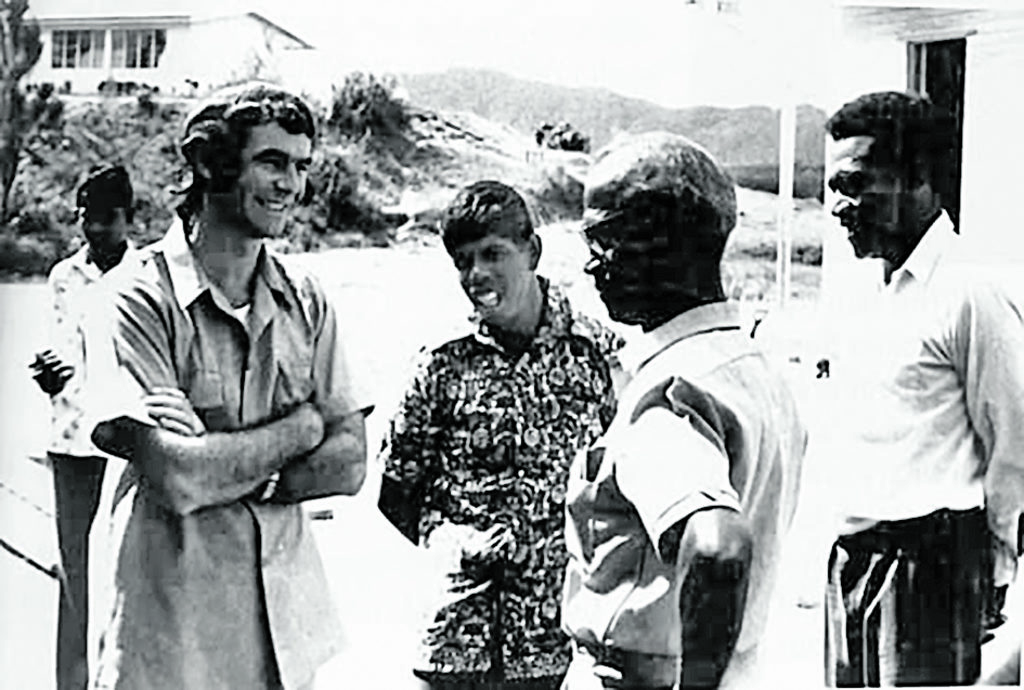

Fr Frank Hoare with Gabriel, Mr Pitch Muttu, and Mr Emosi Caniogo (of Labasa). Picture: SUPPLIED

A view of Naleba church compound in the 1970s. Picture: SUPPLIED

Gabriel’s Nani (grandmother). Picture: SUPPLIED