In last week’s article, ‘A legacy birthed from sweetness’, we explored the early contributions and tireless efforts of the yavusa Navatu, pioneers of sugarcane farming among Fiji’s Indigenous communities. After settling in Tovatova, Tavua, they became known as the Toko Farmers, guided by a devoted man of faith—the late Turaga na Tui Navatu, Ratu Nacanieli Rawaidranu.

This week, we turn to the remarkable legacy of Ratu Rawaidranu and the pivotal role he, together with the late Reverend Arthur D. Lelean and the Toko farmers, played in advocating for an independent and self-governing Methodist Church in Fiji and Rotuma.

Recognising the urgency of the matter, Ratu Rawaidranu called upon members of the yavusa Navatu from across Fiji to gather at Nadogoloa Village in Nakorotubu, Ra. The purpose of this meeting was to develop a plan to repay debts owed by the Fijian Methodist Church to the Methodist Church in Australia, to raise funds for the church’s first independent conference, and to collect 100 kamunaga (whale’s teeth), powerful symbols of honour and sacred promise in iTaukei culture.

These objectives were shared not only by Ratu Rawaidranu, Reverend Lelean, and the Toko farmers, but also by many Methodist divisions throughout Fiji. Yet, at the time, the subject of independence was both sensitive and controversial.

Ratu Rawaidranu and Reverend Lelean recognised the need for strong support from the powerful divisions of Ba, Nadroga, and the Ra circuit to ensure the proposal would be taken seriously and prioritised.

According to theological scholars and researchers of the Methodist Church in Fiji, the Ba and Nadroga division was not only the largest in the country, but the largest Methodist division globally.

Sister Inez Hames, a dedicated Wesleyan missionary and educator in Fiji, affirmed this in her writings and noted that the Ra circuit was a leading force in the drive for independence.

The Ba and Nadroga division covered nearly half of Viti Levu, encompassing the vanua of Serua, Nadroga, Nadi, Ba, and Tavua.

The Tui Tavua, another strong supporter of church independence, had provided the land that allowed the Toko farmers to carry out their work.

The name ‘Toko” was given to this land to reflect the biblical account of Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan River. In that story, the heavens opened, and God proclaimed: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.” The iTaukei Bible renders this as: “Oqori na noqu gone ni Toko, au sa dau lomana vakalevu.”

Jesoni Navara from Verevere Village in Nakorotubu explained that Toko also symbolised the divine calling felt by the yavusa Navatu—a sacred duty to serve God and the church.

Ratu Rawaidranu once expressed that all members of the yavusa Navatu and their supporters in the movement for Methodist independence should be recognised as Gone ni Toko ni Kalou (children of God’s calling) because of their obedience, faith, and unwavering commitment to their mission.

Support for the movement extended across Fiji, with people from Tailevu, Bua, Nadroga, Serua, and Kadavu offering their help.

For Ratu Rawaidranu and Reverend Lelean, witnessing the unity of the faithful and the progress made in Toko and beyond was a source of immense joy.

They believed that this solidarity would carry the Methodist Church in Fiji into the future as a truly independent and self-governing institution.

In 1941, the Toko Farmers convened a meeting where they resolved to hand-over the money and kamunaga they had collected to the divisional minister, steward, and other leaders of the Ba/Nadroga Methodist division.

It was also agreed that, rather than attempting the time-consuming and costly process of visiting every high chief individually to seek their support, it would be more effective to present their appeal at the 1942 annual meeting of the Great Council of Chiefs.

Furthermore, they decided to seek the assistance of students from Methodist institutions — Toorak, Davuilevu, Delainavesi, and Matavelo — to help raise additional funds during their overseas choir and meke tours.

In 1949, the Toko farmers’ proposals were once again brought before the bose ko Viti, then known as the Fijian synod. The call for independence had grown stronger, with an increasing sense of unity among synod members, who urged the Australian Methodist Church to consider Fiji’s case.

Again, in 1954, the divisions of Ba and Ra brought the matter before the Bose ko Viti. Around the same time, the Centenary Church in Suva had been newly dedicated and blessed.

Although Reverend Lelean had by then returned to Australia and Ratu Rawaidranu had passed on, their shared dream endured. Their vision lived on in the tireless work of the Toko farmers.

Ratu Nacanieli Rawaidranu died in 1941 — the same year the Toko farmers successfully completed the objectives set out at the Nadogoloa meeting. The debt to the Australian church had been paid, and the required kamunaga had been collected. On his deathbed, the Tui Navatu said:

“The task I had set out to accomplish for the Kingdom of God has not yet been accomplished within our division of Ba and Ra.”

That task was the full independence of the Methodist Church in Fiji and Rotuma, and the holding of its first conference as a fully autonomous church.

It would take another 23 years for that dream to be fulfilled. In 1964, the Methodist Church in Fiji and Rotuma finally attained full autonomy — realising the vision of a chief whose life was defined by strength, faith, and determination. His dream never withered. His mission never faded.

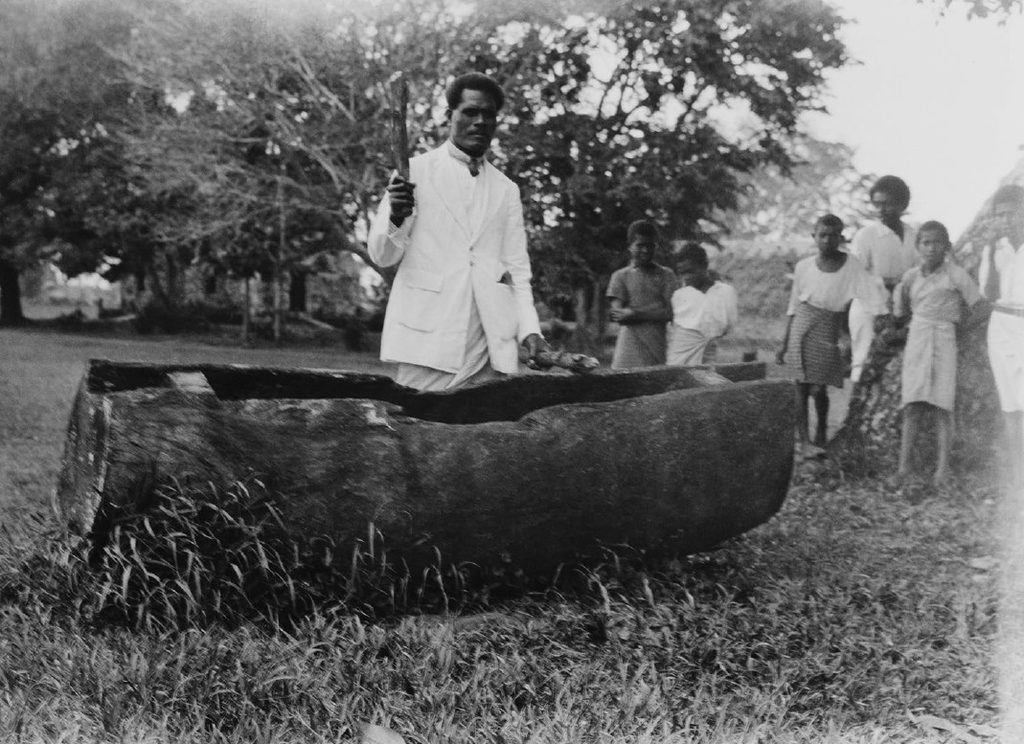

Beating of the church lali at Nailaga Village in Ba. Picture: Methodist Church of Australasia

Above: Ploughing at Nailaga Village, similar efforts such as this were underway at Toko ni Tavua. Picture: Methodist Church of Australasia

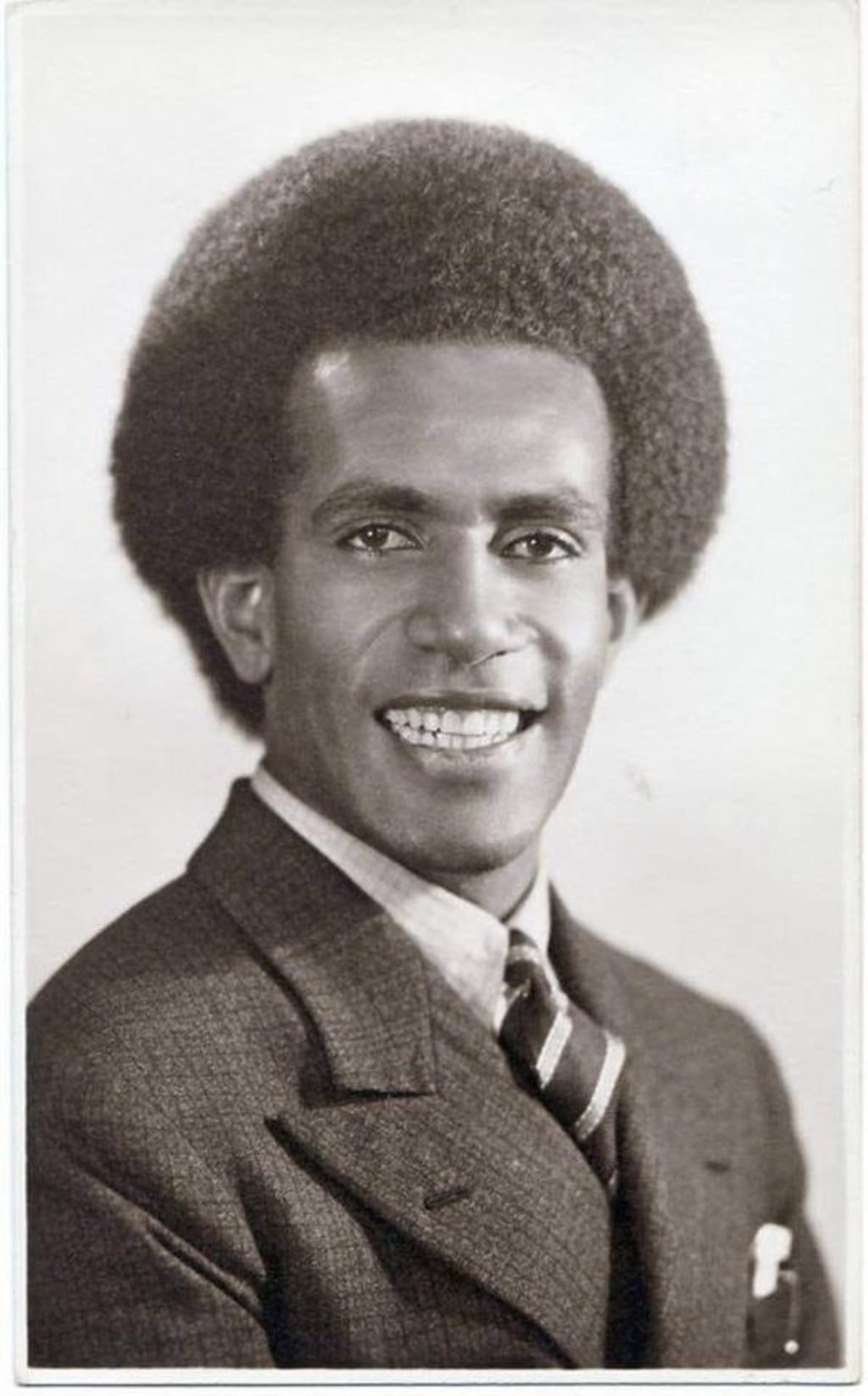

The late Reverend Setareki Tuilovoni from Natokalau village in Matuku, Lau became the first local President of the Methodist Church in Fiji and Rotuma. Picture: FACEBOOK