PART 2

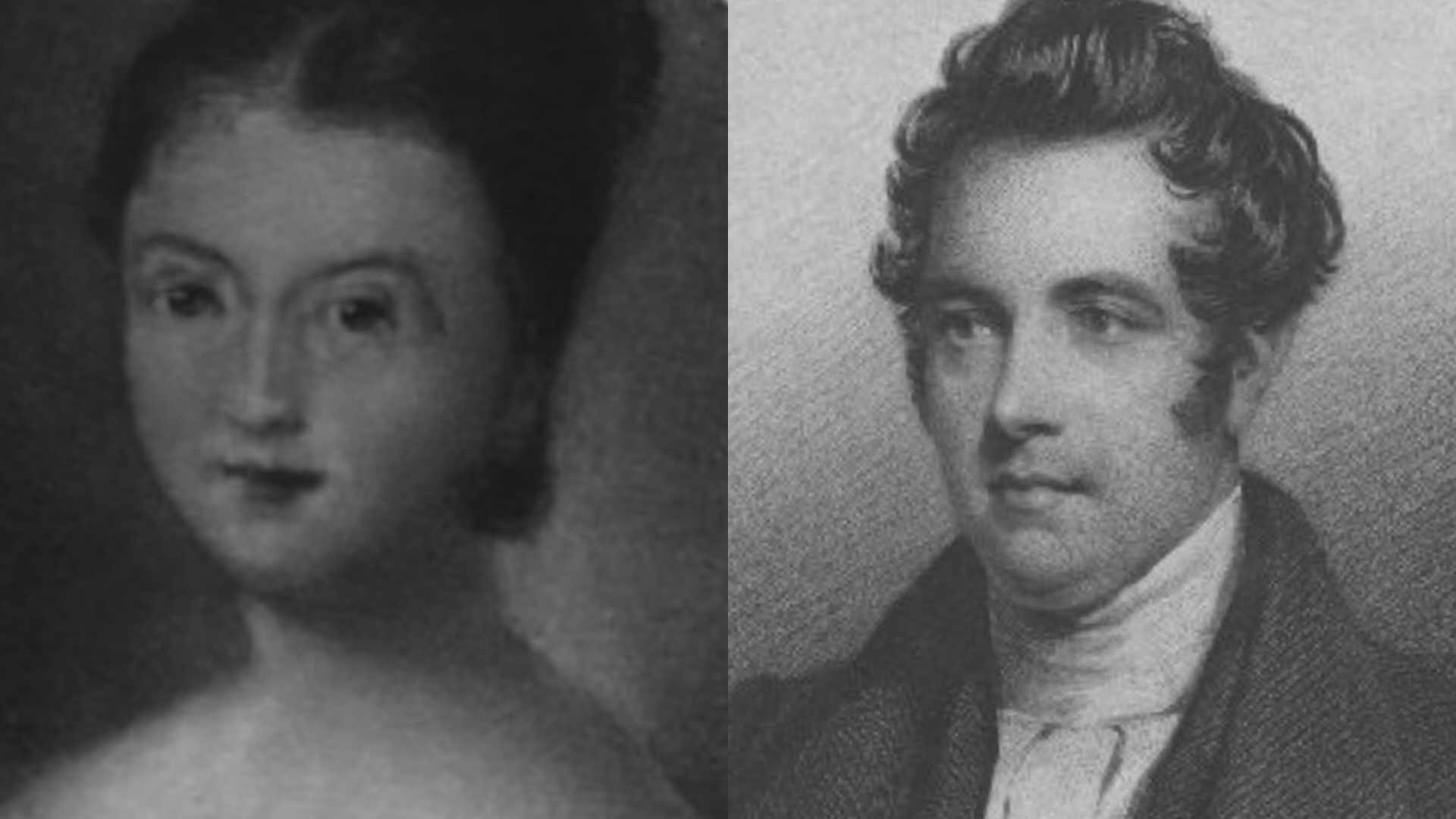

AS time passed in Fiji, Margaret Cargill’s health declined slowly, and Reverend David Gargill had accepted this as a normal state of affair because she always triumphed over any adversity.

In September 1836 she had turned 27 and the Cargills were entering a new phase of spiritual growth. The new chapel was now crowded during service with more of the Tongan community turning to Christianity on the island of Lakeba.

Author, Mora Dickson, in her book titled, The inseparable grief: Margaret Cargill of Fiji,” shared how the Fijians would crowd about the doors and windows peeping inside with great curiosity.

“More and more, both races, arrived at the school when the bell clanged at five am, showing a remarkable aptitude for the new skills of reading and writing,” Dickson wrote.

The number of converts on Lakeba increased every week. However, the mission settlement faced a time of scarcity because only a few schooners navigated the Fijian waters due to its dangerous uncertainty.

During this same year, Margaret’s worry was made easier after the ‘King got around to building a new house’ and when the schooner Active arrived. “The house was a beautiful one and they were very appreciative.”

It was described by Reverend Cargill as the largest and most comfortable native build mission house in the South Sea Islands.

“The mats for walls and floors were of Fijian work, beautifully woven and patterned as was the coloured sinnet which tied the posts and crossbeams, and fine dyed local cloth made curtains for partitions,” Dickson quoted Rev, Cargill as saying.

“Maggie was delighted, at last there was space to set out her things and for her babies to play safely where she could keep an eye on them.”

It was also now possible for her to keep her kitchen in order and train the women who assisted her which proved to be a failure.

Her requirements when dealing with food items were not met and many went to waste.

“Flour went musty, storage bins and jars were left unsealed,” Dickson penned in her book.

The tragedy of four seamen who were captured, baked, and eaten by the natives nearby in which Margaret had earlier been received as guests, dampened her spirits.

But this pushed her to redouble her efforts to bring the women of Lakeba to believe in Christ and turn to a more peaceful way of life.

“Later in the year Maggie was pregnant again, Jane was three and the baby Augusta about ten months,” said Dickson.

“In January 1837 Margaret was thanking her mother for a letter received dated August 1835, two years, and five months on the way.

“Mrs Smith too has been anxiously waiting to hear from her daughter, unaware that the wreck of the Active had created a fatal gap in any regular system of communication.”

Despite receiving extra food supply from the vessel, Victor, the Cargills continued to live on the edge of hardship.

“Pigs were once again taboo; the barter for services and food was an exorbitant as the Fijians could make it, all that remained of their stores was a little sugar and tea,” Dickson said.

“Everything that was not absolutely necessary to the household Maggie put aside to be used for barter; trunks, clothes, cooking utensils, most of their China. “She made bread of arrowroot and molasses.”

Margaret had given birth once more to a girl in June of that year and it wasn’t long before she was pregnant once again towards the end of the year of 1837 which later was once again a girl.

For 11 months, they were alone on the island when the Crosses had left. Margaret had taken up the management of the female school and agreed to be the class leader where she formed her own class from non-churchgoers she knew.

“Quietly and without a fuss, she gathered round herself a class of Tongan women, many of them much older than she was, who during the months that followed grew into a close, warm relationship with her”

When Reverend Cargill had started a voyage round the islands to meet Christian communities, he took Margaret and his children on Fijian canoes where they suffered seasickness.

During the move to the Rewa mission in 1838, Margaret in her ‘fragile woven house’ felt distressed and constantly unsettled. The Cargills were present during the death of a great chief where a ceremony called “veinasa” which lasted for 10 nights was held in Rewa.

This was followed by a royal battle where men threw clay missiles at the women with a bamboo instrument and the women lashed at the men with small cords where shells were fastened at the end.

“During this time there was anarchy and confusion everywhere; the nights were bright with fires and loud with screams, shouts, and the thud of blows,” said Dickson.

“On October 16, three muskets were fired near the mission and a ball whizzed over the head of baby Mary’s nurse. “Increasing familiarity with and affection for the Fijians had resulted in a heightened sensitivity to the dark side of Fijian life.”

It wasn’t long before another war broke out, this time by the Roko Tui Dreketi who decided to go on an expedition to punish a nearby settlement 30 miles from Rewa. This did not stop the work of the mission as it steadily continued, and Margaret’s home streamed with native visitors who were sick, wounded, and aged.

“Even while her sick child demanded unceasing care Maggie nevertheless continued to involve herself in the concerns of others,” Dickson said.

“Tuinadrekeji had another brother, Thokanauto, who admired Margaret Cargill and was especially kind to her.

“He called her his great friend and came constantly to talk to her and ask her advice on many different subjects.”

The year 1840 had been the darkest year for the Cargill family. Margaret was with a child again and was often fatigue, needing frequent rest but continued with her usual duties.

On one occasion she suffered from retching dysentery and was unable to get out of bed. Those who surrounded her did not suspect she was fatally ill.

“Next day Maggie was somewhat better. On the twenty-third Maggie got up and began her usual duties.”

In May, at 4.30 am she woke Reverend Cargill and informed him of her poor health and that the child was soon to be born.

The Reverend was accustomed to what was needed and made necessary arrangements before their two weeks premature ‘stout beautiful girl’ was born.

“For a few hours it seemed as though there had been truth in the view that her pregnancy was the cause of Maggie’s ill health,” Dickson said.

“Then the worst happened she began to haemorrhage.

“Maggie, feeling her life blood flow out her became restless and agitated, a death-like paleness spread over her lovely features.”

It was a few days later when the baby passed on and by this time she had weakened greatly knowing that death was close.

“Seeing the anguish in David’s face she said gently, ‘Come near me, David, that I may bless you before I die’, and threw her arms around his neck and kissed him.”

Her daughters were called in the room and to each she gave a memento, to her oldest Jane who weeped bitterly, she gave her a ring given by her own mother on her wedding day in 1832.

“Margaret with her infant daughter were buried in a coffin covered with dark blue cloth in the temporary house in which she had died.”

It was after the Tongans had ornamented the grave, that a neat strong wooden house was erected to cover it with a bamboo fence enclosing it.

• History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too