Last week we ended when one of the American’s bloodiest encounters with Fijians in the 1800s happened on Malolo Island during the United States Exploring Expedition in Fiji.

In retaliating against the death of two fellow Americans, naval officers got ashore and destroyed crops, bure and canoes belonging to the islanders. According to the website www.navalhistory.org, the landing party also “burned down homes and killed 57 of the islanders”. As a result of the killings, Charles Wilkes, the commanding officer of the Pacific expedition, was tried by a general court martial on the charge of murder and of acting in a “cruel, merciless and tyrannical manner” when he returned to the US.

He was later acquitted. Some personal property that belonged to the murdered (Underwood and Henry) were recovered during the raid in the village of Solevu, Malolo.

“As the attacking party approached the second village, the chief came out to plead that his village had not been involved in the attack. He offered Wilkes some pigs as a ‘peace offering’,” Robert Sprague noted in the paper titled The United States Exploring Expedition in Fiji. Wilkes refused the pigs but later accepted another peace offering after being satisfied the villagers had fully surrendered in front of all members of the expedition.

“On July 27, a small group of chiefs led by a woman came asking for peace, but in keeping with Fiji custom, Wilkes rejected it and demanded that all islanders appear before him,” the Naval History and Heritage Command website noted.

They apologised by getting down on their knees and wailing.

He lectured the islanders before ordering them to replenish his ship with food and water. In his later accounts of the voyage, Wilkes blamed Lieutenant James Alden, commander of the party for not taking proper precautions. The Americans left Fiji, relieved to have done the task they were assigned to do. The Fijians were equally happy that the Americans would not be around anymore to burn their villages or attack them with modern weapons.

Sprague said the US exploring expedition literally put Fiji on the map. He said the surveys that Wilkes compiled were assembled into charts and published in 1845 by the US Navy. “They were not perfect but they were a great improvement over what had existed before. Islands had been discovered and shoals located with precision. Navigation was much safer in Fijian waters as a direct result,” he said. When the American expedition fi nally left Fiji, no Fijian was more heartbroken than their prisoner, Ro Veidovi.

Wilkes final notes on Fiji read: “On taking out final departure from these islands, all of us felt great pleasure”.

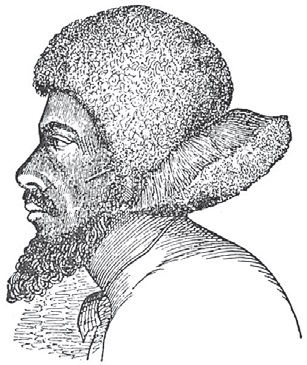

“Vendovi alone manifested his feeling by shedding tears at the last view of his native land.” Ro Veidovi left Fiji aboard the Peacock, which later ran aground off Columbia River when it reached the Americas. The Rewan chief was transferred aboard the expedition flagship Vincennes.

Since leaving Fiji, Ro Veidovi was overwhelmed with grief. However, to help his homesickness he befriended the ship’s crewmen. Ro Veidovi’s name was mentioned in the accounts of a few of them.

He told them about love in Fiji, taught them a few Fijian vocabularies, and went over stories of how a mysterious flood caused by Fijian gods once destroyed the islands. In the two years in which Ro Veidovi was travelling with the Americans, some readings suggest he was friendly and this earned him the respect of his captors.

As a result, Wilkes honoured his memory by naming the island we know today as Vendovi. Ro Veidovi was particularly very close to one of the crew. He was a pilot, Benjamin Vanderford, who had learned to speak Fijian in the few years he spent in Fiji during the lucrative bêche-de-mer trade.

But when Vanderford died unexpectedly, Ro Veidovi’s heart was broken, the crewmen said. Some historians believed that Wilkes named an island in Puget Sound in the US “Vendovi Island,” in an attempt to “humour a sorrowful Ro Veidovi”. contracted pulmonary tuberculosis and died two hours after arriving in New York. His head was removed from his body and his skull was later cleaned and handed over to museum officials.

His headless body was then buried at the Brooklyn Naval Cemetery and later exhumed and re-interred at the Cypress Hills National Cemetery in New York.

According to the web page New York City Cemetery Project, in the early 1830s the US Navy established a burial ground on the eastern edge of the Brooklyn Naval Hospital (1838) which became a leading centre of medical innovation, developing new techniques in anaesthetics, wound care and physical therapy.

The two-acre Naval Cemetery was used from about 1831 to 1910 and was the burial place for more than 2000 people of all races and creeds, most of them officers and enlisted men of the United States Navy and Marine Corps.

“Interred here were two Congressional Medal of Honor winners, Vendovi, the ‘Fijian Cannibal Chief’ who died in the Naval Hospital in 1842, and individuals from more than 20 different countries,” the web literature read.

The 1880 description of the Fijian chief, from the List of Specimens on display in the Anatomical Section of the United States Army Medical Museum then read “Vendovi”, chief of one of the Fiji Islands. His skull was numbered Specimen 292.

But 30 years before it ended up in the Army Medical Museum’s List of Specimens, one collector had labelled it the skull of “the Feejee Chief and Murderer”. American historian, Ann Fabian, said Ro Veidovi was aboard one of the ships of the United States Exploring Expedition that sailed into New York Harbor on June 10, 1842.

She said while controversy surrounded Wilkes’ expedition, for the way he meted out unjust punishment resulting in the killing of villagers from Malolo, he eventually received accolades for his work.

The charts his surveyors produced and the 40-odd tons of natural specimens the expedition’s scientists collected were outstanding. Among these “Fiji” specimens was Ro Veidovi’s skull. According to Fabian, while the ships waited for a pilot in the waters off New York, Charles Pickering, a senior member of the scientific corps, wrote to an American skull collector, Dr Samuel George Morton, and told him to “travel quickly to New York”. “Our Feejee Cheif [sic] is on his last legs and will probably give up the ghost tomorrow,” Pickering told Dr Morton. “…it would be well worth your while to come on immediately, for such a specimen of humanity you have never seen, and the probability is, that you may never have the opportunity again.”

At this point, Ro Veidovi was dying and there were already plans by authorities to keep his skull after he passed. “Pickering knew that his ‘specimen of humanity’ from Fiji was particularly interesting to an ‘anthropologist’ like Morton, who was trying to sort the world’s diverse peoples into races,” Fabian said. “He also knew that any existing systems of racial categorization would have to be adjusted in light of what he discovered on his voyage with Wilkes.”

At the time, Morton’s studies had deduced there were fi ve standard races in the world – the Ethiopian, the Mongolian, the Malay, the American, and the Caucasian. Judging from Ro Veidovi’s features, the Fijians were “puzzling” because they had “dark skin and curly hair but sharp features”. This suggested they could have been “a race of their own or a mix of many”. The Wilkes expedition was an astounding success.

It managed to collect thousands of animal and plant specimens, created 200 nautical charts of the Pacific and confirmed the existence of a continental landmass in the Antarctic Ocean. Today, Vendovi Island, one of the remote islands in Washington State named after Ro Veidovi of Rewa, is popular for its collection of unique plants and birdlife, frequented by tourists who love nature, forest hiking and bird watching.

Those who visit her shores know little of the man it was named after, where he came from and how he came to be. Ro Veidovi’s story is more than a tale of crime and punishment or cause and effect. It is more than just a record of, perhaps, the first Fijian to set foot on the western frontier. It is a story that records one of the first historical links between Fiji and the US. Furthermore, it could also be seen as a narrative of the expansion of great powers from the continent and how they jostled for territory and made violent contacts with the indigenous people of the Pacific.

Lawyer, Ro Alipate Mataitini, summed it up this way in one of his past articles on the subject of Ro Veidovi.

“He was a victim of his own generation, subject to the atrocities of the time like murder, abuse and cannibalism, memories of which can only be expunged by the telling of the truth, rather than an embellishment of what were really acts that should never be condoned,” Ro Alipate said.

History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor