Part 2

Last week Part 1 ended when Ro Veidovi of Rewa, the brother of then Roko Tui Dreketi, was wanted for the death of several American beche-de-mer traders who were killed on Ono Island, Kadavu in 1834.

In 1840, the American ship, Peacock, was in Rewa waters, when William Hudson received a message from the commanding officer of the United States Exploring Expedition in the Pacific, Lieutenant Charles Wilkes (on Vincennes) to arrest Ro Veidovi.

According to one historical account, Patrick Connell, an Irish beachcomber who had settled on Viti Levu, was the person who dobbed Ro Veidovi in. Connell told Wilkes the Rewa chief was involved in a “treacherous incident” in 1834.

That year, American merchant ship Charles Doggett had hired some islanders, including Ro Veidovi, to help in the harvesting and curing of beche-de-mer on Kadavu.

During the enterprising trip, a rumour began circulating among the Fijians that the ship contained items of value. In an attempt to seize the ship and get the coveted “valuable objects” Ro Veidovi, with the help of accomplices, killed 10 people on Ono.

Eight of them were Americans. He met his punishment when the US naval expedition arrived in Fiji in 1840, under the command of Wilkes.

Hudson was surprised by Wilkes’ orders for Ro Veidovi’s arrest. The chief had helped the Americans many times during their expedition up the Rewa River.

What Hudson did was invite an entourage of chiefs from Rewa to the Peacock with the intention of arresting Ro Veidovi as soon as he stepped on board. On the appointed day, the Rewan party came on board, but Ro Veidovi did not turn up.

ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY.

As a result, Hudson held the chiefs hostage.

“The poor queen was the most alarmed and anxiously inquired of Phillips (Cokanauto) if they were all to be put to death,” noted Wilkes in his expedition records.

“Phillips was equally frightened with the rest, and it was observed that his nerves were so much affected for some time afterwards that he was unable to light a cigar that was given to him, and could not speak distinctly.”

To calm down the startled hostages, Hudson provided them with entertainment. In the end, they told Hudson that Ro Veidovi was indeed “a dangerous character” and they would be happy “to see him removed”.

It was later decided that Qaraniqio and another chief should go ashore, arrest Ro Veidovi and produce him on the ship alive.

The selection of Qaraniqio was perfect for Ro Veidovi had been his rival for some time.

The temptation to “get rid of so powerful adversary was an opportunity” although that adversary was his blood.

Qaraniqio went to capture Ro Veidovi on the afternoon of May 21. After negotiating with him, they turned up aboard the Peacock the following morning.

Veidovi acknowledged his guilt and was informed that he would be taken to America as a prisoner.

Wilkes said Roko Tui Dreketi agreed that Ro Veidovi deserved to be punished and to go to America himself. In his journal on May 22, 1840, the Wesleyan missionary, Reverend David Cargill told Hudson the Fijian chiefs “were fully sensible that it was just that Veidovi should be punished”.

“Veidovi was in irons. He acknowledged that his crime was great and that he merited punishment,” Rev Cargill wrote.

“Captain Hudson informed me that he intended to take him to America to show him many of the vessels of war that he might form an idea of the extent of the power of the Americans in punishing those who kill or molest the crews of any of their vessels.

“He wished also to introduce him to Missionary Societies, to teach him Christianity and to imbue his mind with the love of virtue,” Rev. Cargill said. Not everyone agreed with Ro Veidovi’s arrest.

The chief had helped the Americans many times during their expedition up the Rewa River.

What Hudson did was invite an entourage of chiefs from Rewa to the Peacock with the intention of arresting Ro Veidovi as soon as he stepped on board.

On the appointed day, the Rewan party came on board, but Ro Veidovi did not turn up.

As a result, Hudson held the chiefs hostage.

“The poor queen was the most alarmed and anxiously inquired of Phillips (Cokanauto) if they were all to be put to death,” noted Wilkes in his expedition records.

“Phillips was equally frightened with the rest, and it was observed that his nerves were so much affected for some time afterwards that he was unable to light a cigar that was given to him, and could not speak distinctly.”

To calm down the startled hostages, Hudson provided them with entertainment.

In the end, they told Hudson that Ro Veidovi was indeed “a dangerous character” and they would be happy “to see him removed”.

It was later decided that Qaraniqio and another chief should go ashore, arrest Ro Veidovi and produce him on the ship alive.

The selection of Qaraniqio was perfect for Ro Veidovi had been his rival for some time.

The temptation to “get rid of so powerful adversary was an opportunity” although that adversary was his blood.

Qaraniqio went to capture Ro Veidovi on the afternoon of May 21.

After negotiating with him, they turned up aboard the Peacock the following morning.

Veidovi acknowledged his guilt and was informed that he would be taken to America as a prisoner.

Wilkes said Roko Tui Dreketi agreed that Ro Veidovi deserved to be punished and to go to America himself.

In his journal on May 22, 1840, the Wesleyan missionary, Reverend David Cargill told Hudson the Fijian chiefs “were fully sensible that it was just that Veidovi should be punished”.

“Veidovi was in irons. He acknowledged that his crime was great and that he merited punishment,” Rev Cargill wrote.

“Captain Hudson informed me that he intended to take him to America to show him many of the vessels of war that he might form an idea of the extent of the power of the Americans in punishing those who kill or molest the crews of any of their vessels.

“He wished also to introduce him to Missionary Societies, to teach him Christianity and to imbue his mind with the love of virtue,” Rev. Cargill said.

Not everyone agreed with Ro Veidovi’s arrest. Some believed he was unfairly treated.

Sprague said it appeared that Ro Veidovi’s surrender was motivated by the Rewan chiefs’ attempt to gain some advantage by “close association with the American expedition”.

While last week’s story (part 1) said beachcomber, Connell dobbed on Ro Veidovi, Sprague said Whippy may have been the one who incriminated the chief in a six-year-old massacre to help make the white men, especially Americans, more powerful in Fiji.

On June 10 1840, the Americans travelled up north to Somosomo to get the signature of Cakaudrove’s chief, the Tui Cakau. Wilkes came across difficulties because the chiefs could not be persuaded “for fear of a like detention with Vendovi”.

By mid-June, Sprague said the members of the expedition started to lose the favour they had for the Fijians.

On their visit to Lau to get the consent of the Tui Nayau, Wilkes described the “King of Lakemba” this way: “…he is a corpulent, nasty-looking fellow, and has the unmitigated habits of a savage”.

He added that Lakeba was “dirty and badly built”, but had some large houses, and in it were “numbers of ugly women and children”.

Hudson took the treaty to Bua too. But he had to first mediate in a fight between two rival chiefs before he successfully got the natives to sign the documents.

It seemed Fijian chiefs always signed the agreement regardless of the difficulties the Americans initially faced when getting them to put their names on paper.

Wilkes said they were, however, “very quick in discerning what will please those they wish to conciliate, and readily accede to their views.”

Relations between the Americans and the indigenous Fijians worsened when a stranded ship that was part of the expedition and her crew were captured in Solevu (Bua).

The loss of the ship hampered the expedition. Wilkes was upset.

“My conditions not being complied with, I determined to make an example of these natives, and to show them that they could no longer hope to commit acts of this description without receiving punishment,” he said with anger.

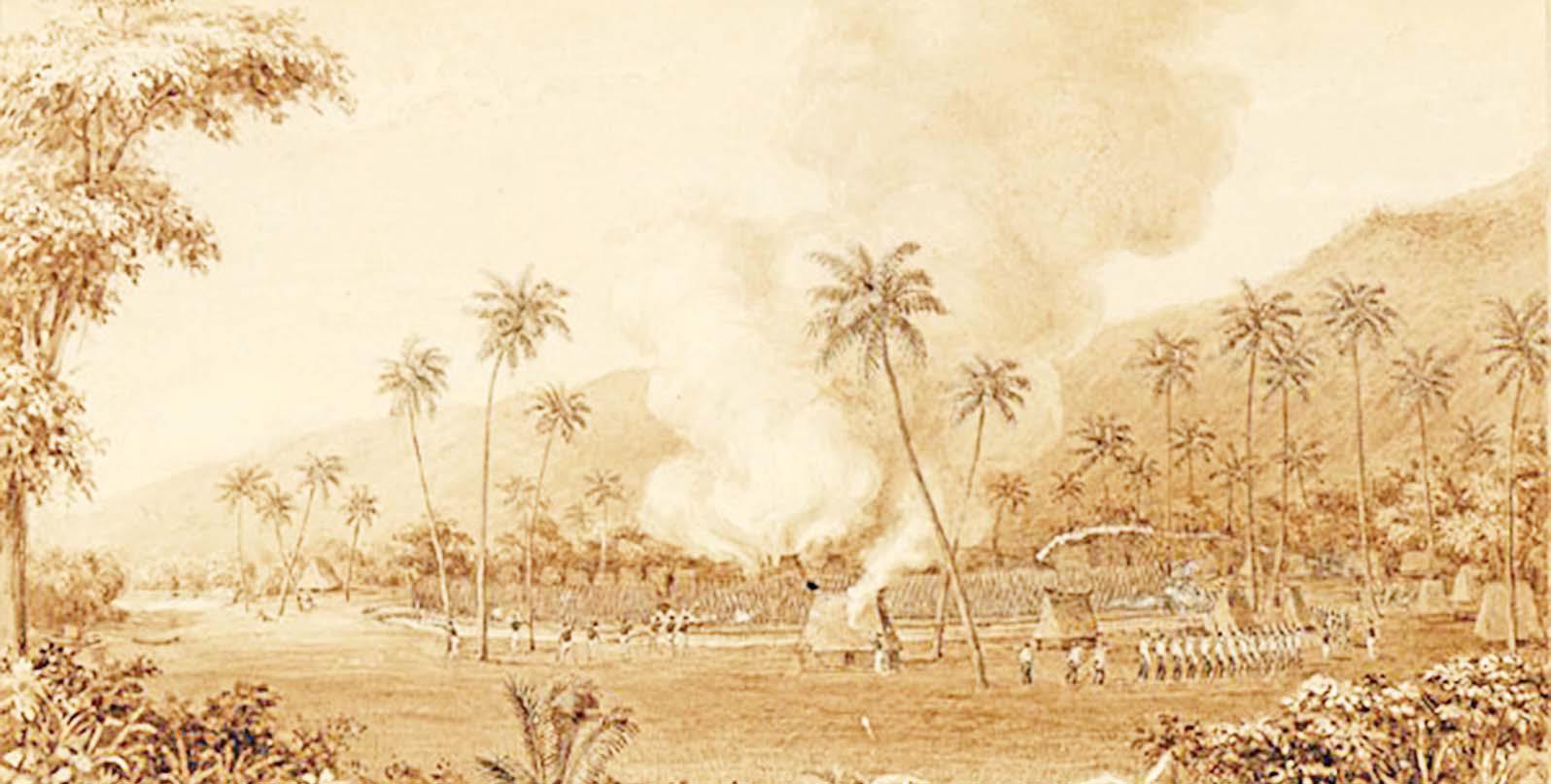

He ordered some of his officers to go ashore and burn down the village. There was no resistance from villagers.

“The infliction of this punishment I deemed necessary; it was efficiently and promptly done, and, without the sacrifices of any lives, taught these savages a salutary lesson,” a weary Wilkes said.

The Naval History and Heritage Command website said Wilkes immediately called together a party of men from his and Captain Hudson’s ships and rowed more than 60 miles in the evening to the site of the theft.

“On Wilkes’ appearance the next morning, the islanders abandoned the boat, but its contents were gone. In retaliation, Wilkes ordered Hudson to burn the thieves’ village,” the website said.

“Having thus demonstrated the power of his anger, Wilkes released two hostage chiefs from nearby friendly towns and sent them off with valuable presents, demonstrating the power of his friendship. Word of the incident spread rapidly through the islands.”

The expedition’s bloodiest encounter happened when the Americans were on Malolo Island.

Two crew members got killed while negotiating for food and water with islanders on the beach. They had ignored Whippy’s warning on Ovalau and went ashore without being armed.

“I could not but feel a melancholy satisfaction in having it in my power to pay them these last sad duties, and their bodies had been rescued from the shambles of these odious cannibals,” Wilkes said he inspected the two dead bodies.

Dead were Joseph A. Underwood and Wilkes’ nephew, Wilkes Henry, the only child of his sister.

He wept openly and it was said it took him a few days before he could think properly again.

The next day some crewmen buried Underwood and Henry in unmarked graves to prevent the bodies from being dug up and desecrated by the people of Malolo.

Alfred Agate, the artist who sketched drawings of the expedition, conducted the burial service.

The expedition left America in 1838 before camera and photography was first introduced into the US from France. Artists performed the role of photographers.

Wilkes sent ashore a group of sixty crewmen to burn the villages of Solevu and Yaro.

Some of the villagers, mainly the women, children and elderly, sought refuge on the highest point on the island.

The Americans destroyed crops, bure and canoes belonging to the islanders.

According to the website www.navalhistory. org the landing party “burned down homes and killed 57 of the islanders”.

Some historical records note that the Americans used the latest model of guns that had just been released before their departure.

They were classed as Elgin Cutlass pistols.

Only 150 of these unique pistol knives were made by C.B.Allen for use by the navy on the Wilkes expedition.

As a result of the Malolo killings, Wilkes was tried by a general court-martial on the charge of murder and of acting in a “cruel, merciless and tyrannical manner” when he returned to the US. He was later acquitted, his wrongs overshadowed by his triumphs.

Some personal property that belonged to the murdered Underwood and Henry were recovered during the raid in Solevu.

“As the attacking party approached the second village, the chief came out to plead that his village had not been involved in the attack. He offered Wilkes some pigs as a “peace offering,” Sprague said.

Wilkes refused the pigs, but later accepted another peace offering after being satisfied the villagers had fully surrendered in front of all members of the expedition.

“On July 27, a small group of chiefs led by a woman came asking for peace, but in keeping with Fiji custom, Wilkes rejected it and demanded that all islanders appear before him,” The Naval History and Heritage Command website noted.”

They apologised by getting down on their knees and wailing.

He lectured the islanders before ordering them to replenish his ship with food and water.

In his later accounts of the voyage, Wilkes blamed Lieutenant James Alden, commander of the party for not taking proper precautions.

The Americans left Fiji, relieved to have done the task they were assigned to do by the US Congress.

The Fijians were equally happy that the Americans would not be around anymore to burn their villages or attack them with superior Elgin Cutlass pistols.

Part 3 Next Week

- History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor.