IMRANA Jalal has kept a letter from the Public Service Commission in 1991 where her application for paid leave to study Gender and the Law at the prestigious Stanford University in the United States was rejected.

It serves as a reminder of the very patriarchal type of thinking she had been battling with all her life.

After being awarded a US Fullbright Scholarship which, unfortunately, would not cover all tuition and living costs, Imrana applied for paid study leave — standard practice for employees at the Attorney-General’s Office (AGO) at the time.

“I was anticipating leave with pay so that I could continue to meet my debts while studying,” she recalled.

“The permanent secretary (PS) of the Public Service Commission at the time rejected my application, even though the AGO had supported it.

“He sent me a standard issue government memorandum stating that, ‘women’s issues are not a priority for this government’.

“I kept that letter and later resigned from the AGO.

“I think it’s fair to say that the permanent secretary has lived to regret the day he made that statement.

“I wrote about it in the foreword to my book later.

“He was an MP in one of the Parliaments I lobbied much later to pass the Family Law Act and he has said to me many times ‘why won’t you ever let me live that down?’

“He was a charming man of course, but oh so misguided about women.

“Although I may forgive, I shan’t forget.

“The PS is typical of the men of his generation and genre, many of whom were national leaders.

“I bear him no ill-will.

“But like other defining moments in my life as a feminist, it shaped my thinking, and the zeal with which I dedicated myself to changing the law I suppose.”

When Imrana told her father, Abdul Jalal, that she had applied for a scholarship, he asked her if she was intending to do a PhD. When she responded that she was planning to enrol in a Masters in Women’s Studies, “he retorted ‘What is that?’

He could not believe I would waste two years of my life doing feminist studies. He could not understand it.”

Imrana, fortunately, received two scholarships from the Australian and Queensland Associations of Women Graduates which enabled her to attend Sydney University and where she graduated with a Master of Arts in Gender Studies in 1992.

“Money was tight, so I worked part-time as a waitress at the Tandoori Palace in central Sydney.

“I returned to work in Suva in 1993 at Jamnadas & Associates with my then husband Dilip.”

Imrana had enrolled for gender studies partly to provide the Fiji Women’s Rights Movement (FWRM) — an organisation she co-founded in 1986 — with a better theoretical understanding of its activities and it was her intention to turn her Master’s thesis into a book.

Researching for the book was gruelling.

Nothing had been documented and Imrana travelled extensively, with financial support from The Asia Foundation while pregnant with her first child, Gibraan, throughout the Pacific, to collect primary data.

From 1991 to 1996, she worked on the book, on and off, during two pregnancies.

“My editor, Bess Flores, remarked once that she knew well the parts of the book that I had drafted whilst breastfeeding.

“She happily edited those sections out or toned them down!”

Law for Pacific Women: A Legal Rights Handbook was finally completed and published by the FWRM in March 1998.

The 700-page book was designed to make the law accessible to legislators, policy planners, non-lawyers and activists with the research covering the human and legal rights of women in Fiji, Nauru, Tuvalu, Kiribati, Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga, Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands.

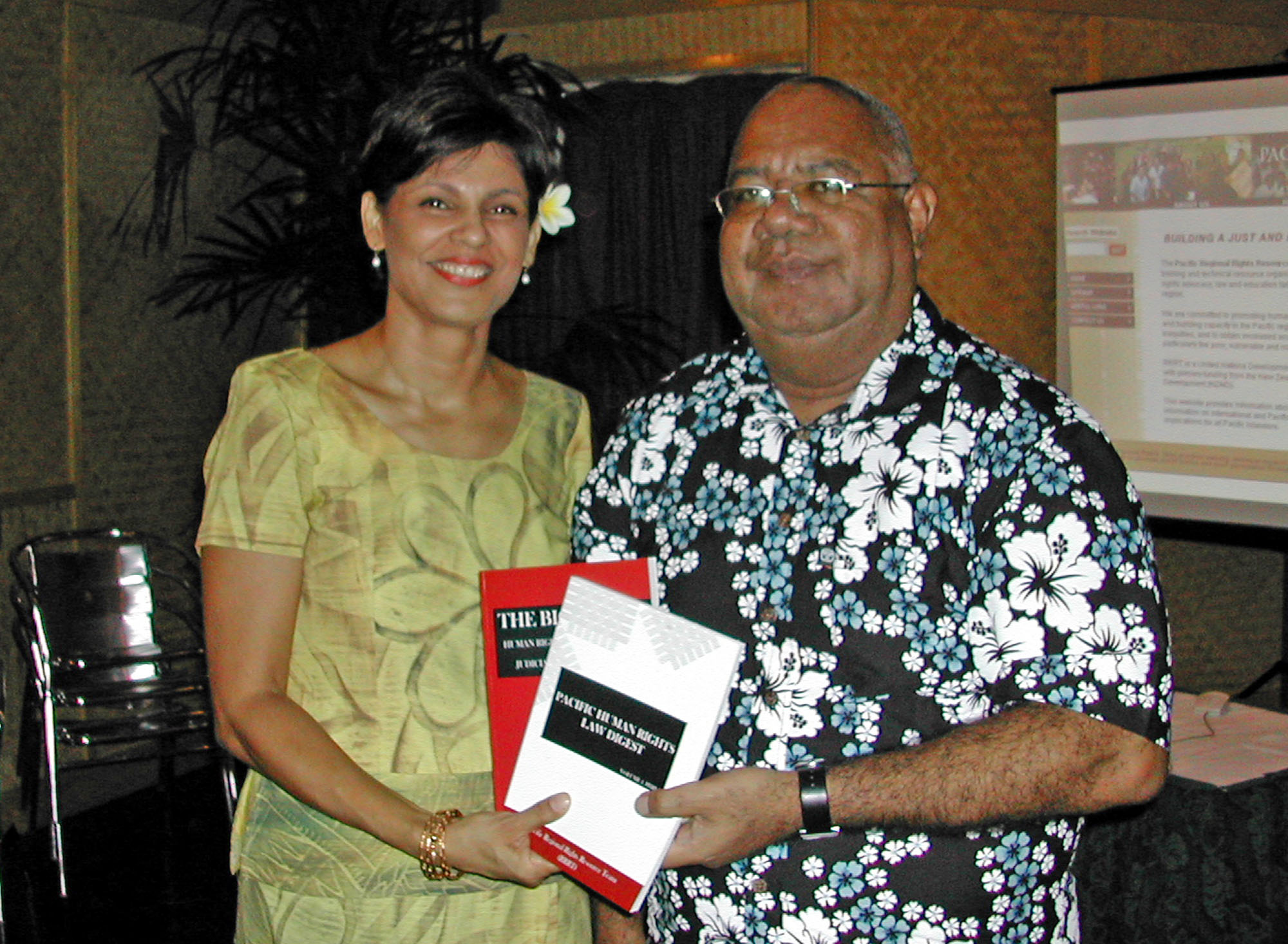

Imrana’s book has been one of many catalysts for policy and legislative change throughout the Pacific, spurred on by the work of the FWRM, as well as through the Pacifi c Regional Rights Resource Team, an organisation also co-founded by

Imrana.

“All proceeds from the sale of my book go to FWRM as long as FWRM remains committed to feminism, the rule of law, human rights and democracy.

“The funds are now part of the FWRM Jalal-Lateef Trust Fund, augmented by Shireen Lateef’s legacy to FWRM.

“My close friends Sufi Dean and Annette Sachs Robertson are entrusted to ensure that the goal endures in the event of my death.”

After fighting patriarchy for more than three decades, cofounding three organisations to enhance women’s rights, serving on the Fiji Rugby Union

board, raising three children, working at the Asian Development Bank for seven years, being appointed to the Inspection Panel of the World Bank in January 2018, and becoming chair until December 2020, making her a vice-president of the

World Bank — one would think that Imrana was ready to hang up her gloves.

Nothing would be further from the truth.

“One of my next big projects, after I retire at the end of 2022 from the World Bank, will be to use some of those trust funds to find FWRM a permanent home.”

An important part of Imrana’s life is mentoring and encouraging younger women feminists, whom she communicates with on a regular basis.

She said many had passed through the FWRM doors, and had become close friends.

“These are the women who bring feminist leadership to governance at different levels.

“Amongst them are Virisila Buadromo, Priscilla Singh, Gina Houng Lee, Nalini Singh, Shayne Sorby, Raijeli Nicholl, Vandhana Narayan and others.

These younger women are part of the future of Fiji.

“Who knows, maybe one day we will have a Cabinet line-up not unlike that of the new leadership in Finland?

Wouldn’t that be something?! After all, the men haven’t done such a great job, have they?”