One day in 1984 in a quaint shop along bustling Cumming St, a young boy in his early 20s received his last lessons in photography at Art Studio.

He held a blanket over his head, locking his Mamiya camera in the dark before clicking the press button.

In those days, one loud shot would produced a single negative four by five inch in size. “Great. Now you can take photos,” the boy was told.

From then on, between 1pm and 2pm daily, while his boss went for his midday prayers, Atu Rasea, would take passport photos.

That job lasted three years and it launched a sterling career in photography that continues at The Fiji Times to this very day.

But before working at Art Studio, Rasea worked for a while at another Cumming St shop — Island Studio.

Here he got introduced to the ghostly world of darkrooms. For those who don’t know, darkrooms were special rooms where photographs were developed from films in the ‘good ol’ days.

Rasea remembers the first time he entered one. “It was a scary moment. I knocked on the door and entered into total darkness. It was cold, smelled of chemicals and the only source of light was a red one,” Atu reminised.

“I man from Kadavu whom I later knew as Watisoni Keve was inside. He had a machine and a light shooting on a white sheet of paper.

Nearby where three trays and a tap that had running water.”

“I saw photos appear in the developer tray and finish in the fixer. I was told to wash the final product in the last tray and hang them out for drying. That was my first experience in a darkroom.”

At Island Studuo, Rasea learned everything about developing photographs, preparing him for his first encounter with cameras and his later jobs.

In 1987, three years after first joining Art studio, Rasea worked at The Daily Post as its first photographer.

“I love those days and I remember my first front page photo like it was just yesterday,” he said.

“There was a meeting of the Great Council of Chiefs at the Suva Civic Centre and I snapped a shot of the late Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara and Sitiveni Rabuka.”

In those days, photography was basic. Cameras had no fancy automated functions. There was a lot of thinking behind each click.

Rasea said a photographer carried his manual inside his head. “We had to look at our subject, the quality of light and manually figure out what shutter speed and aperture setting to use.”

“Nowadays, cameras have auto settings. Things have digitised so you click and get your photos instantly. You can even manipulate photos during editing. Taking photographs is not as interesting as how it used to be back then.”

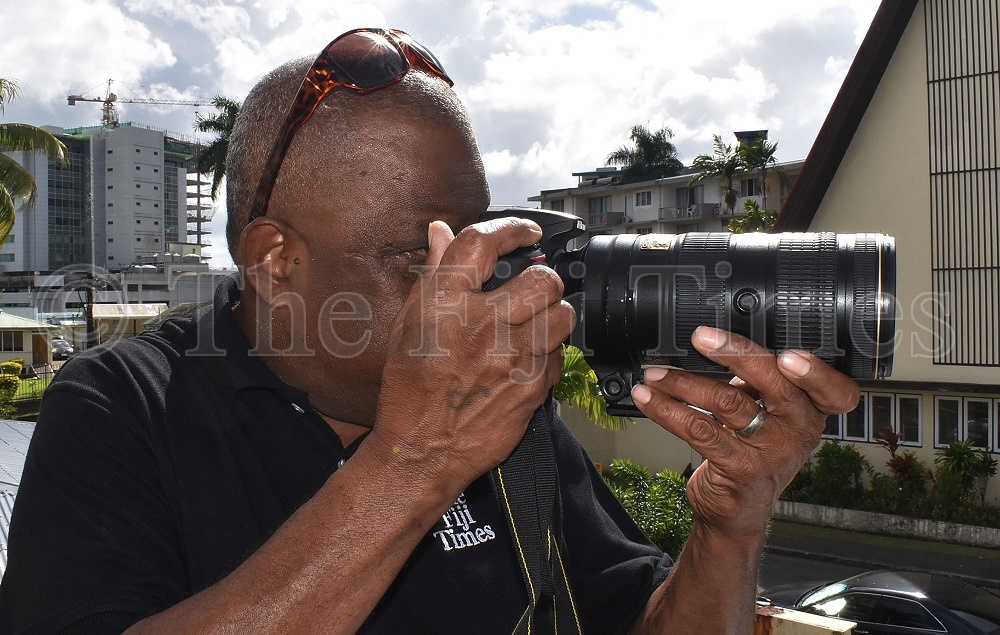

Rasea describes photography as an art and a photographer’s job as “telling a story though photos”.

He says a good picture is one that narrates a story without uttering a word.

“A painter tells a story by putting his imagination on canvas while a photographer tells his story by putting his imagination on a captured moment in time.”

“We are storytellers, just like any journalist, but our stories are not in words but told in the subject we capture through our lenses.”

The veteran photographer has photographed countless community, national and international events.

To get generations of newspaper readers the best photos, he has swum across rivers, climbed mountains, braved the cold and rain, faced the scorching sun and worked for endless hours during the rage of cyclones.

There have been a few times when his life was in grave danger. But he survived them all.

Some highlights of his colourful 38-year career include covering events related to the May 19, 2000 coup and the November 2, 2000 mutiny at the Queen Elizabeth Barracks.

He says he continues to stick around because of his great passion for a job that has allowed him to travel, meet people, and better understand the world.

“Last year, during one of my assignments fromer PM Sitiveni Rabuka asked me saying, “hey! you are still around? When will you ever retire?”

“I told Mr Rabuka that as look as my eyes were opened, I would continue to work.”

That is the same rare calibre of dedication and commitment that many in the news media have every day.

It gives them purpose, to work, and a motivation to do it tirelessly. Whether they are photographers, journalists or sub-editors, media professionals work their utmost best to ensure that Fijians get to know what happens around them. “I am old now and at the tail end of my career (laughs) but I am learning every single day, on the job,” Rasea says.

“That is my secret. I strive because there’s always something new to learn. When you wake up each day, never ever think it’s over. Get up and go because each new day is a blessed opportunity to learn something you didn’t know the day before.” Rasea has ome a long way. But he never forgets his humble beginnings and the people who helped him.

“I salute the family who used to own the photo studio at Cumming St where I worked. I thank them for teaching me a skill that has set me on this long winding journey.”

“I also thank people who first introduced me to the world of the media. I wouldn’t be where I am today without names like Samisoni Kakaivalu, Dan Bolea, Mika Turaga, Torika Tora, Jale Moala, Peter Lomas and Stan Ritova.”

As an advice to budding photographers and journalists Rasea says: “This field is definitely not for the fainthearted. You will be sworn at, assaulted, ridiculed publicly, criticised and shamed. There are days when you’ll feel like quitting – take it easy and have patience. Listen.”

“You story, your photo, even if it changes and touches one single heart is your reward. We are here to tell a story, somebody’s story, with the hope that it will bring change and a brighter future.”

• September is the month on which The Fiji Times was born back in Levuka in 1869. As a 153rd anniversary tribute, The Sunday Times will bring stories told by our newsroom frontliners throughout the month.